An Artist’s Own World: Gustave Caillebotte at the Art institute

Gustave Caillebotte. The Pont de l'Europe, 1876. Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Genève. Image courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum. Photo by John R. Glembin.

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

This June the Art Institute’s major summer exhibition, Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World, will present the Impressionist’s work in the context of the era and the social circles in which he lived. Caillebotte (1848–1894) is closely associated with his monumental painting of a French street scene on a gray and inclement day, Paris Street; Rainy Day, a work that is the crown jewel of the Art Institute’s permanent collection as well as this exhibtion. The show promises to expand how visitors see the artist’s own life and what inspired him, allowing us to appreciate intimate elements of Caillebotte’s world while also presenting questions about what the artist himself saw and wanted viewers to see in his paintings. Curious about the every-day, despite his own privileged background, his radical perceptions and depictions are quite relevant today.

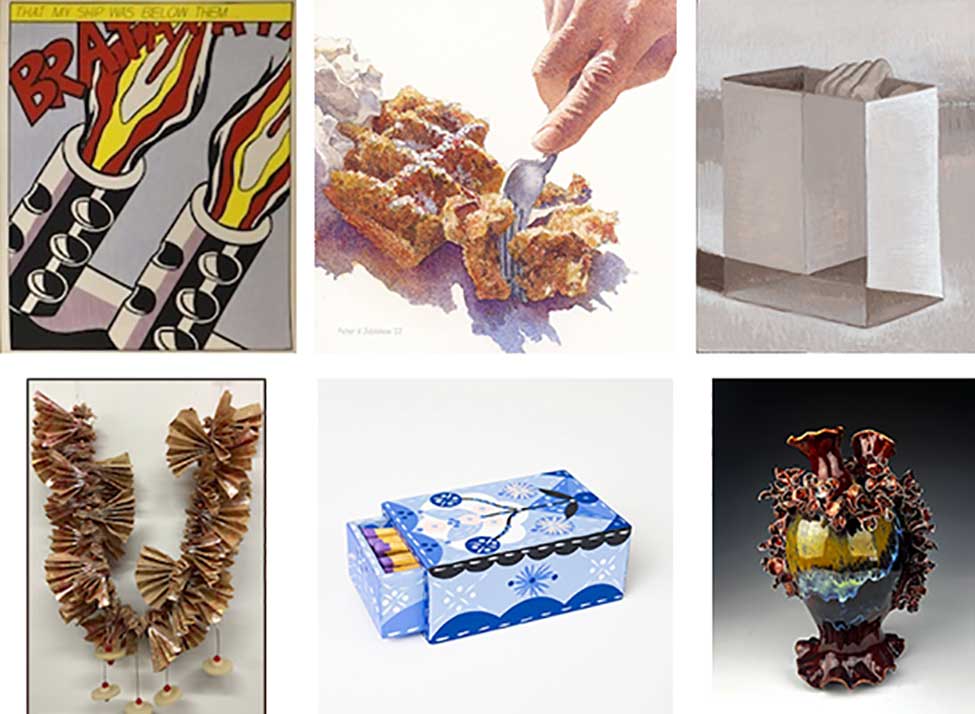

This exhibition, which opened in October 2024 at Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, includes more than 120 works—paintings, works on paper, photographs, and other ephemera from throughout Caillebotte’s career. In addition to recognizable works like Floor Scrapers and Paris Street; Rainy Day, the show presents lesser-known but pivotal works like the Musée d’Orsay’s recent acquisition, Boating Party, and the Louvre Abu-Dhabi’s The Bezique Game, as well as many works from private collections that are rarely seen by American audiences.

Gloria Groom, Chair and Winton Green Curator, Painting and Sculpture of Europe, The Art Institute of Chicago took time this spring to give us a preview of what we can expect from Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World.

Gloria Groom, Chair and Winton Green Curator, Painting and Sculpture of Europe, The Art Institute of Chicago. Photo by Clare Britt

CGN: How did this exhibition come together? What will visitors see, in addition to Paris Street: Rainy Day?

Gloria Groom: Caillebotte is a figure painter, first and foremost. The Art Institute of course owns the granddaddy of all of his paintings, Paris Street: Rainy Day, and it is such a remarkable work because really it’s the first and last multi-figural painting at this scale. Everybody kind of knows the painting, but they don’t know the man. That’s what we wanted to flesh out. We were able to amass a lot of new archival material and get into family archives and really identify the people in his paintings. As a result we realized most of the people are men, so he had a real focus on a subject that most Impressionists wouldn’t be doing, because men weren’t commercially viable [as subjects]. We wanted to focus on that.

Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877. The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. Worcester Collection.

CGN: Caillebotte was an Impressionist, but what set him apart from his contemporaries?

He was born in 1848, right during the French Revolution of that year. He watched Paris go from having a king, to the monarchy collapsing, then to the Second Republic. What the republic brings with it is a lot more freedom, but at the same time anxiety, because he grows up and he’s painting and taking classes during the Franco–Prussian War. For men it was a complicated time, fighting and getting beat by Germans. His interests were not only in the men of his social class, which was upper middle class, but also the people that worked for him, the workers, the gardeners, the people who were scraping down the floors in the room that was going to be his studio in Paris.

He’s also not like the Impressionists because he actually lives with his family and gets along fine with them. He accepted his wealth, but he didn’t want to be just known as a wealthy dilettante. He really throws himself into whatever he’s doing, be it gardening, racing boats or building boats. We wanted to show he was a man of his era.

Gustave Caillebotte. Balcony, about 1880. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the private collection/Bridgeman Images.

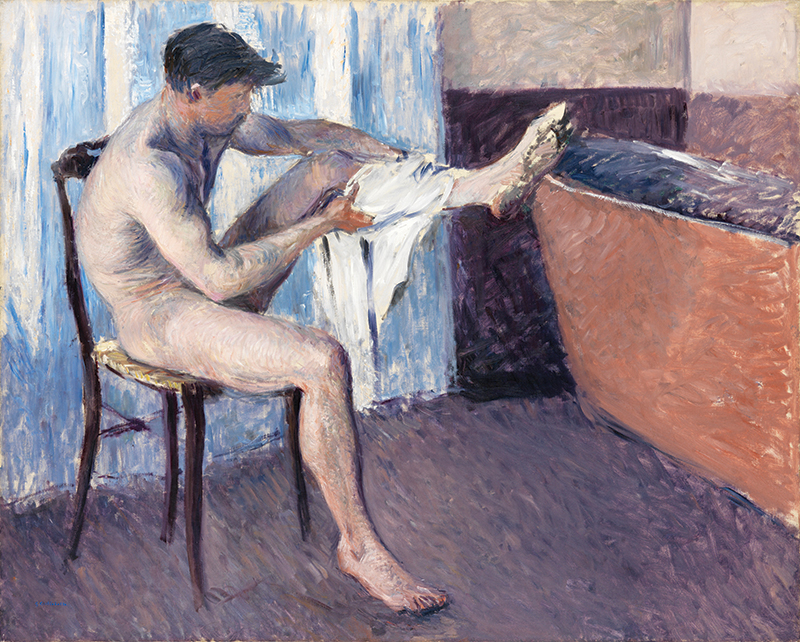

CGN: What was so unusual about how he observed and depicted male subjects?

GG: Men had clubs–like the sailing club, as an example–to belong to, but women did not. Caillebotte liked to be with other males in the Impressionist circle. He esteemed women artists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, but he liked to be in groups and he liked supporting them through his financial wealth, through his talents as a painter. We are really expanding on what he did by spending time in these circles. It’s hard to paint men and make them look interesting, but he’s a real colorist and he’s interested in decorative patterns. So you get portraits that aren’t as austere as one might think. And he uses his male friends as his models.

CGN: There are few direct gazes I see in these paintings of men. He’s really observing them, whatever they’re doing. They’re not sitting for a portrait or even necessarily paying attention to him.

GG: Right. There are only a couple that you get the sense of portraiture. And those are really the ones that ended up in those collections, since most didn’t sell and ended up with family. The idea of detachment is very Baudelairean and something quite modern in the last part of the century. The male gaze is very different, because it’s looking at males. Even when he’s looking at women, there’s a kind of detachment. When you compare a Renoir painting of a woman to one by Caillebotte, any day of the week you’ll see there’s a big difference between the way they’re expressing the feminine in art. He’s really more interested in showing men. He was surrounded by men, he grew up with three brothers and lived in a household of men–he lived with his brother after he left his parents’ house, when they both died. So he is happiest and most comfortable it seems, through his paintings, with these male companionships.

Gustave Caillebotte. Floor Scrapers, 1875. Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Gift of the Caillebotte heirs through Auguste Renoir, 1894. Photo courtesy of Musée d’Orsay, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Franck Raux.

CGN: Did Caillebotte’s subject matter alone qualify him as radical, or was it something else?

GG: I think he was radical not just in his male portraits, but in everything. The Floor Scrapers was considered radical. The thing that really made him stand out was his technique. It looked like it came from the tradition of painting where you do drawings, then you do sketches, then you find the final composition, because some of them were large scale, not as large as ours, but bigger than a regular Impressionist landscape. He painted in a way that suggested he spent a long time with it, as opposed to the impressions of the Impressionists, and that painting style made him popular. His subject matter was still rather radical because he would zoom in on things.

One of the criticisms of our painting at the Art Institute was, why would you make a subject so banal on that scale? It doesn’t deserve that scale. He was considered a more traditional artist, and at the same time a very radical artist because of the foreshortening and because of the subjects he chose, but the way he painted was more legible and accessible than what we call the flickering brushstrokes of a Monet or a Pissarro.

Gustave Caillebotte. Man Drying His Leg, about 1884. Private collection. Photo by Lea Gryze, Berlin. © Private collection, Berlin, 2024.

CGN: It sounds like he didn’t fit that easily with the other Impressionists.

GG: It’s when he’s painting landscapes in water that he becomes an Impressionist, but when he’s painting figures, it looks more traditional. We’ll have a lot of preparatory drawings in the exhibition, for our Paris Street: Rainy Day and The Floor Scrapers and others. People will be able to see that he, like Seurat and like so many artists who are considered modern, starts with observation and drawings and then eventually composes the final painting. But I think the big story is his insistence on painting figures, and men in particular. It’s the radicalness of his way of seeing men.

CGN: What do you think Caillebotte was trying to say or capture in his subject matter?

It’s narrative, but it’s not. He sets us up. Even Paris Street: Rainy Day, it looks like you can read the scene. And when you start trying to figure it out, you don’t know what they’re looking at. They’re not looking at each other, but they’re together. It’s cinematic but it’s not yet giving you the caption that you need. And the name he called it, Paris Street: Rainy Day–he’s not telling you what to think either. That’ll be fun. It will help us understand our painting, which we associate with Chicago. I think it’ll give us the context through the other modern works to better understand it.

#

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World

Jun 29–Oct 5, 2025

The Art Institute of Chicago