Constructing Surprises: Wallace Bowling

Wallace Bowling, Champion

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

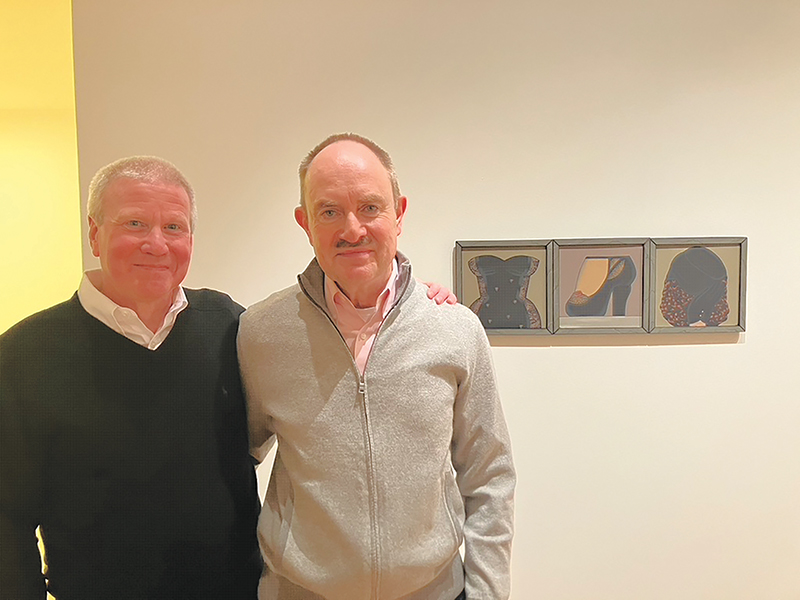

Wally Bowling enjoyed a career as an architect for over 30 years, all the while living and working in proximity to his life partner Douglas Dawson’s eponymous gallery in Chicago. When I first began working at CGN many years ago, I got to know both Dawson and Bowling. Dawson’s gallery fit with the community of galleries that were primarily contemporary, even though he specialized in ancient and historic tribal art from all corners of the world. Dawson closed the gallery in 2017, however elements live in their gorgeous vintage Edgewater apartment overlooking Lake Michigan, which I recently visited on a late Monday afternoon this past winter. Upon stepping off the elevator onto the private floor, you can feel the weight of the art’s history and the care and preservation the couple have shown for it. From room to room remarkable objects are primely placed–pots from Africa, linear furniture and symmetrical pottery from Japan, a collection of stone tools. Excellent talking points, we discussed the consideration of form, shape, and structure, things that Bowling is attuned not just due to his architectural background but because he is also an artist, something he has been actively embracing for the past decade.

I had not seen Bowling very often since the gallery closed, but Bowling invited me to his home so I could view some of his recent artworks he has been assembling, pieces that he calls constructs. Bowling has retired as an architect, but his creative instincts still find an active outlet in his art. His first gallery exhibition was in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky a decade ago. As much as it is a form of expression, art making can also solve a design problem, such as how separately interesting objects can fit together to make something entirely new.

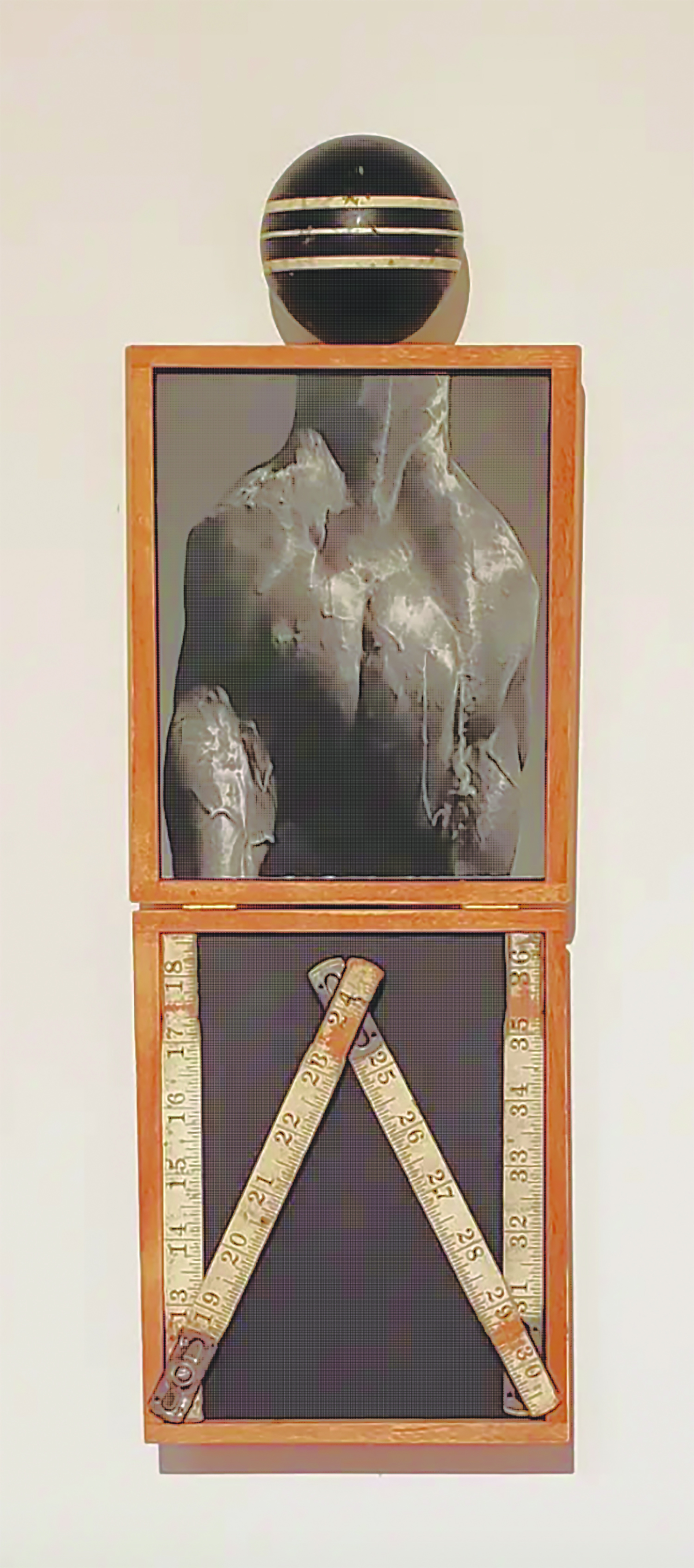

Bowling’s constructs are placed throughout a set of ebonized bookshelves lining the full length of a wall in the lakeside dining room. None is particularly large in scale, but each features many curious, yet mostly familiar, utilitarian elements–knobs, hooks, latches, handles. The additions of found photographs, game pieces and text unify the disparate pieces into something new, almost ideally matched.

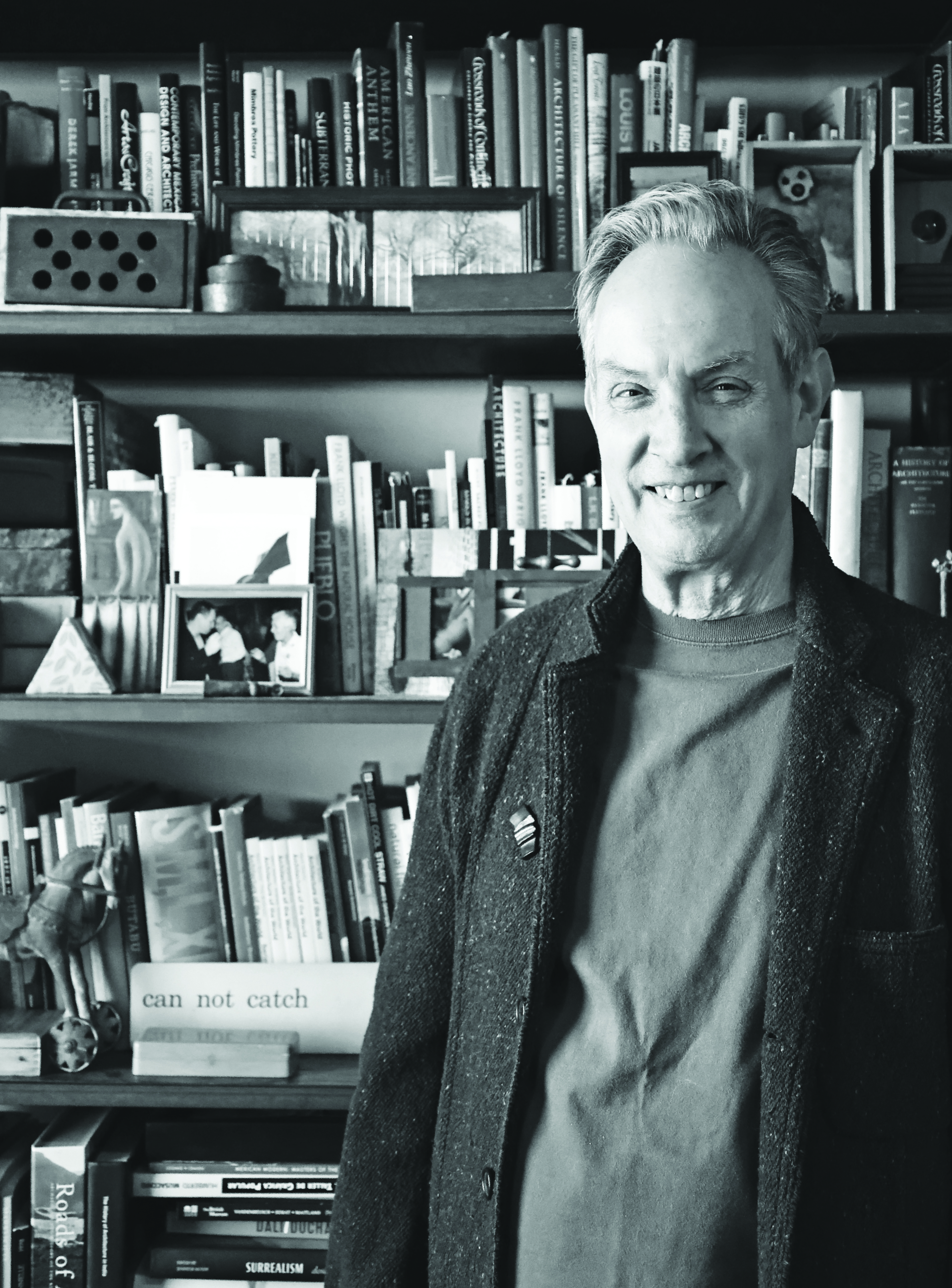

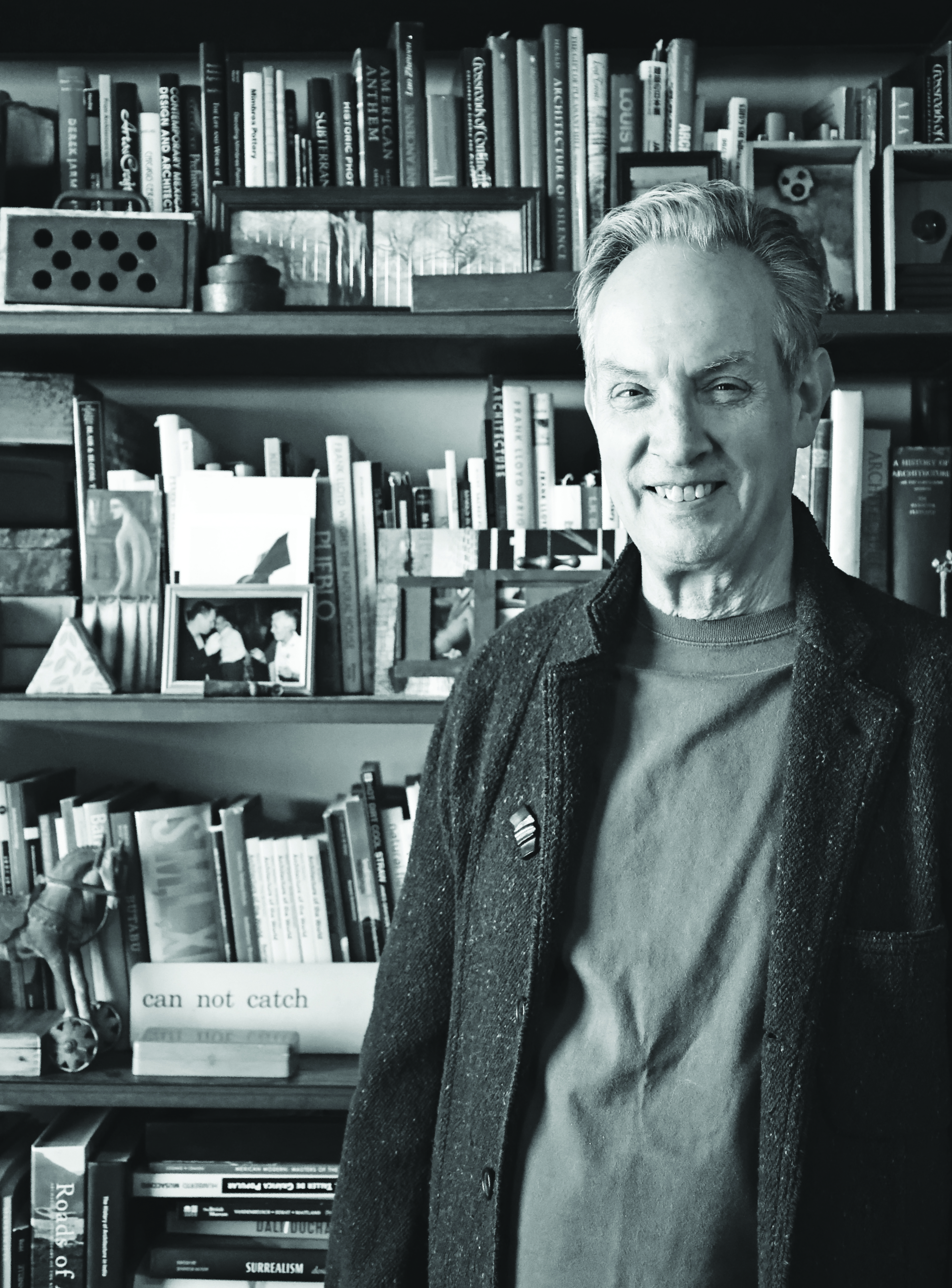

Wallace Bowling at home in Chicago. Photo by CGN.

Several works are made from cigar boxes, containers Bowling says he used to find easily when traveling between Kentucky, Chicago, Madison and his and Dawson’s farm in Iowa. “What was interesting is that all the cigar stores were keen on recycling these boxes. Each of them had a charity that they wanted to donate the few bucks that you’d buy them for.” This resourcefulness impressed Bowling, and the architect in him was excited when he realized that the factory molds he had found in another shop fit neatly into the boxes, like they were meant to be despite disparate purposes. Finding and acquiring the molds made Bowling wonder what each one would have been for. Initially Bowling says, “The architect in me would sit down and do a drawing, and I would foolishly try to find the pieces that I wanted for it. I got over that really quickly.” A fit makes itself known, but it cannot be forced. Bowling says he is glad he bought what he could over the years because many of the antiques stores and flea markets he sourced his boxes and molds from are no longer around. While he could search more easily online today than years ago, he says that’s not the same as happening upon one object in a market and then waiting to encounter the piece that will make its match.

Browsing the collection of constructs along the bookshelves, it’s as if I am looking over a set of family photographs, not because of the images within many of the boxes but because of the thematic and visual similarities I see. It’s as if they are a family–not an immediate or nuclear one but generations gathered at a reunion. I start to guess which pieces came before the others. Bowling’s process, while methodical and precise due to his architectural roots, is deliberate but I don’t think he has limited himself to thematic blocks, due to the serendipitous nature of sourcing his materials. Some of his constructs showcase tools that are no longer widely used, others show off the beauty of an obsolete factory mold. When I remark that many are phallic, though he points out there are nude women here and there as well. Others hint at a secret sadness. While others have attachments which might be harmful, if not handled properly. Each one is a departure from its material’s original purpose and contains a surprise.

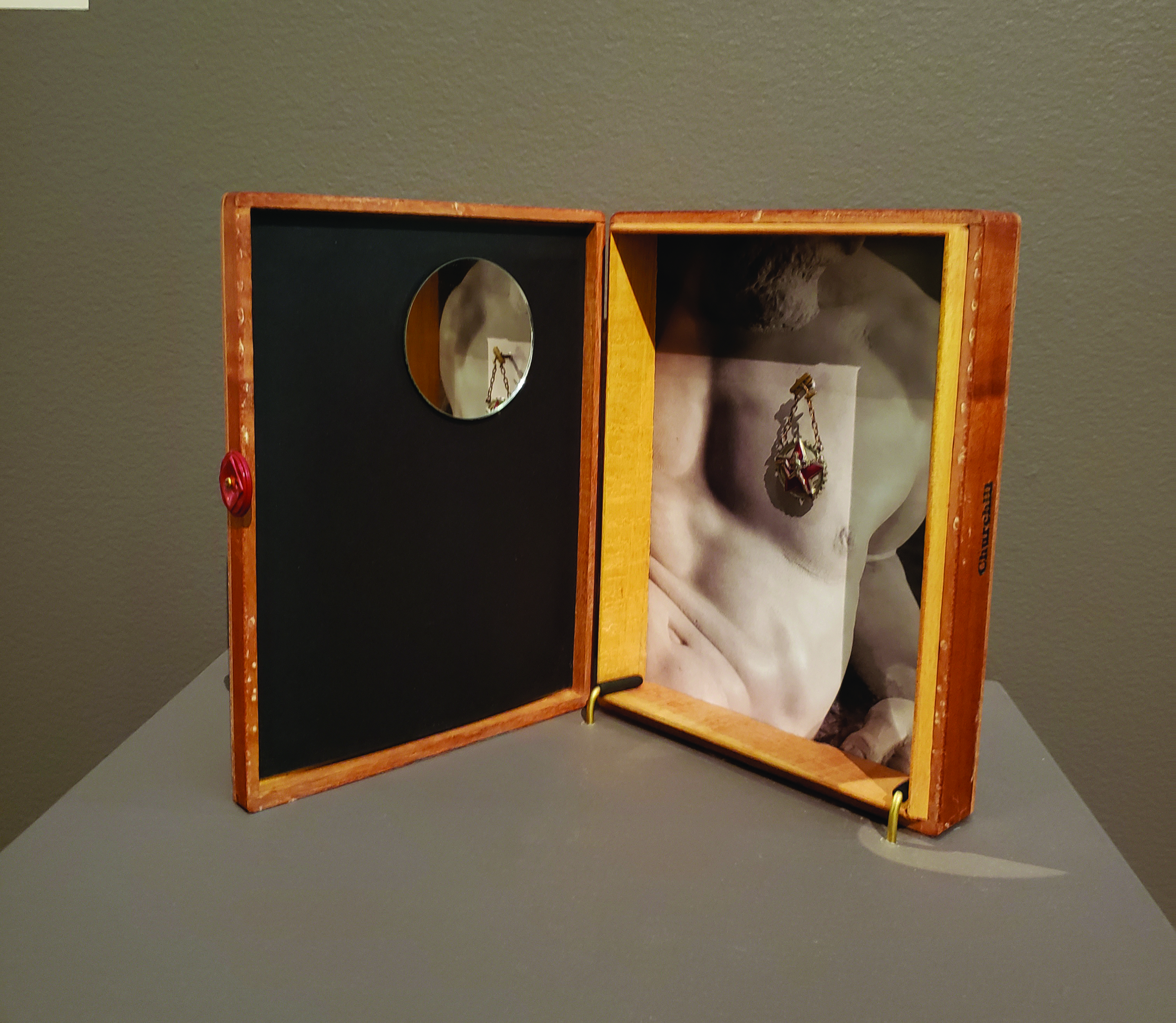

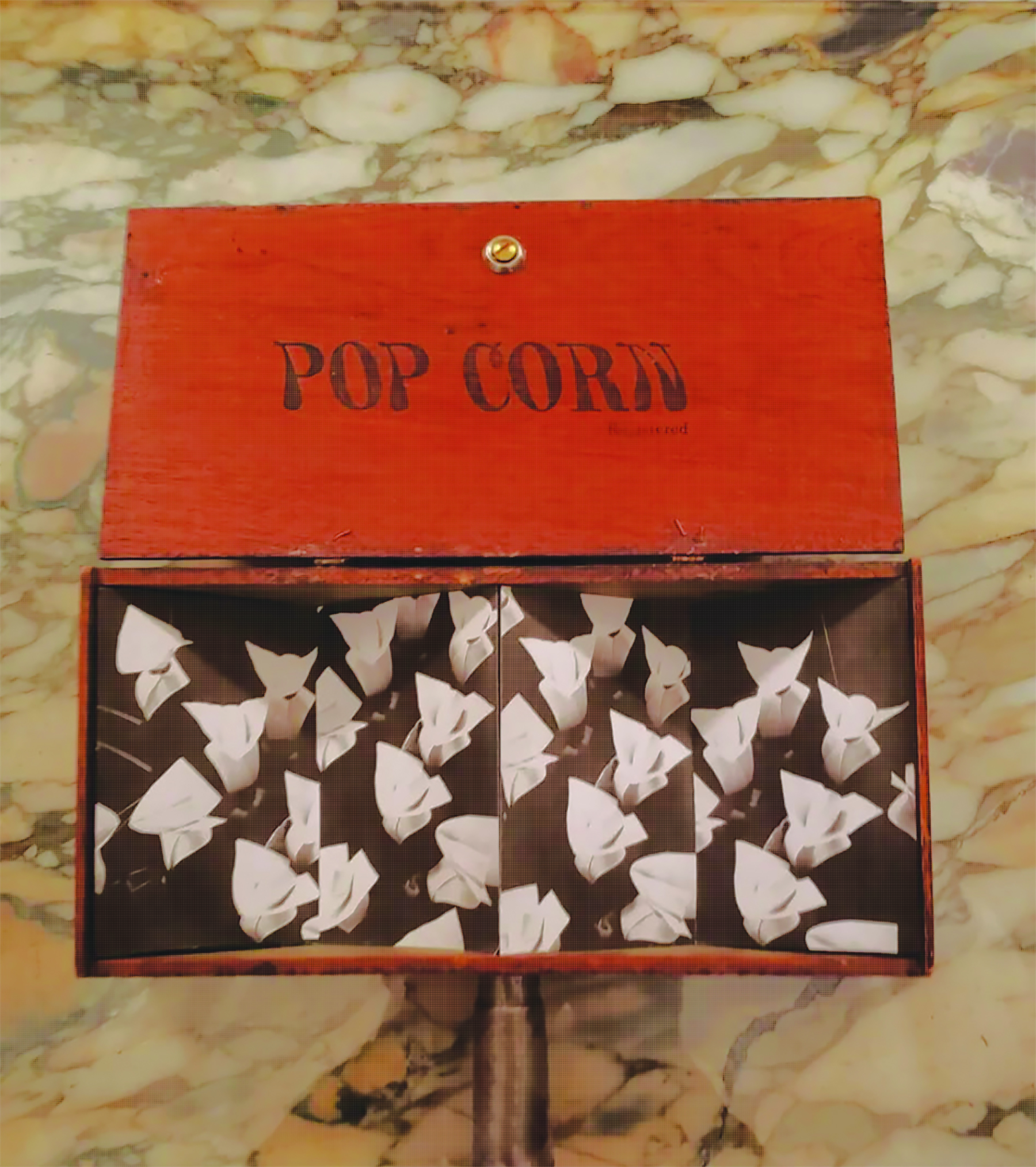

Wallace Bowling, Amended cigar box with vintage aerial image of nuns’ cornettes.

Wallace Bowling, Amended cigar box with vintage aerial image of nuns’ cornettes

Bowling shares a story about a simple thin box with a hinged lid that was once a popcorn box, perhaps for storing kernels. He joined a handle on the side of the box at the suggestion of a friend, and he pasted an image to the inside, revealed to anyone who opens it. The amended and reassembled photograph is a vintage aerial shot of nuns’ cornettes.

Bowling hails from Kentucky, but for many years now he and Dawson have spent about half the year on their farm in Harpers Ferry, Iowa, where they enjoy rural quiet and the chance to live and work outdoors, and the other half in Chicago. Traveling between their two homes, and a bit beyond, means Bowling frequents galleries and museums on both sides of the Wisconsin and Minnesota border, which has led to several institutional relationships over the years, from the Racine Art Museum, to the Chazen Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as well as the Lanesboro Art Center in Lanesboro, MN. Bowling and Dawson have long been world travelers, but now with the gallery closed they have the freedom to slow down and spend longer stretches in Iowa, where Bowling can work out of his rural studio and take time to tinker and experiment with his designs. His artistic process is similar to solving a design problem in that he has to take the measure of a project and then find what elements go together best. He also likes to take his time. Sometimes, Bowling shares, he starts with a sketch. Other times he shops his own studio, where the shelves are filled with tubes and boxes and organizers intended for tools and assembly pieces.

Much of Bowling’s eccentric interests come out of the many art forms he has dabbled in: welding, ceramics, painting, and a lot of his collection he has dubbed “the museum of the discarded” as it’s filled with things you might find in an antique shop. He brings something home because it has a really unusual shape, he explains, or a patina. He points to a large, rusty, collapsed oil container he scavenged when traveling abroad. When some vendors nearby wondered what he saw, he explained he collects things he sees as interesting. “You never know what you might need it for,” he admits. Just in case, Bowling keeps numerous Bakelite radio knobs, drawer pulls, plumbing fixtures and other items on hand in his studio. “On their own they don’t mean a lot, but frequently they’re the perfect piece.”

Bowling has been considering building a really large construct. “I might do a whole series of boxes that would make a landscape, and they could be filled with architectural objects and images.” He imagines they look like small domiciles, once again referencing his architecture career. “These shapes, they’re perfect. Even how they’re arranged they come across with a strong architectural influence, but they’re definitely their own creations.” Somehow, this artist will find how to fit them all together.

Wallace Bowling, Exquisite Horse