Designs on Collecting: Architect Dirk Denison

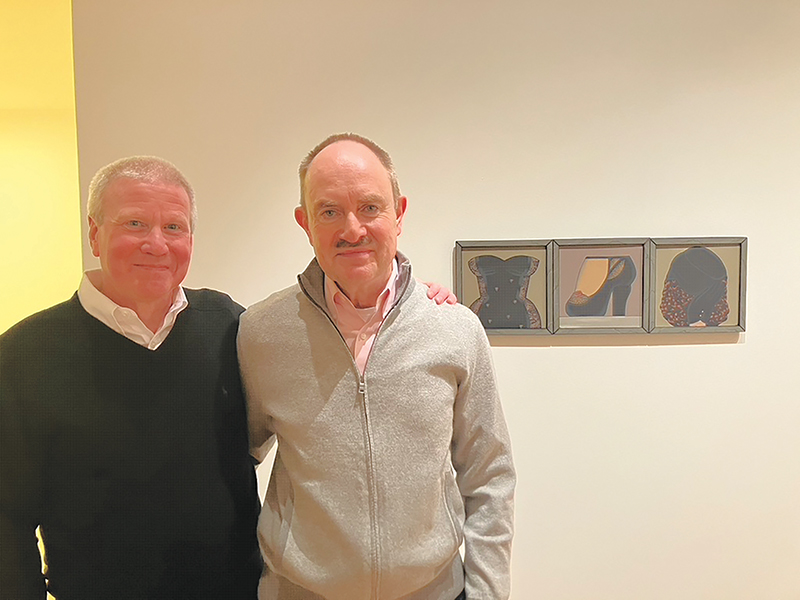

Dirk Denison with a painting by Leasho Johnson

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

Dirk Denison has been a practicing architect for over 30 years. Originally from Detroit, Denison and his designs, both residential and commercial, are well known to many Chicagoans. Though his reputation is national, CGN readers are likely familiar with the gallery spaces he has constructed to showcase much of the city’s best art. A professor at the IIT College of Architecture and the Director of the Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize, Denison also runs his own award-winning firm, Dirk Denison Architects, based in Chicago’s West Loop. I recently spoke with Denison about his art and design background, his connection to Chicago and what it’s like to design spaces for art as well as introduce his own clients to the world of art collecting.

CGN: Tell me where you grew up and how you were first introduced to art as well as architecture.

Dirk Denison: Well, I grew up around Detroit in a home that was filled with art as well as artists, so it’s always been a part of my life. My experience was enriched by going to Cranbrook for school in suburban Detroit, which has not only the world famous art academy, but also has an elementary and high school. I was fortunate to go through all the way, from nursery school through graduation. And actually both my parents went there as well. They met in high school. I left, of course with this great appreciation for design from a very holistic standpoint. If you have visited Cranbrook, the Saarinens* worked as a team, a family, and they designed the buildings and the furnishings and the tapestries, even the setting landscape that surrounds it. So, I arrived in Chicago with all of that not really consciously a part of my working reference, but it is certainly intuitively embedded in who I became as an architect.

*Note from Cranbrook: Saarinen House is Eliel Saarinen’s Art Deco masterwork and the jewel of Cranbrook’s architectural treasures. Designed in the late 1920s and located at the heart of Cranbrook Academy of Art, from 1930 through 1950 Saarinen House served as the home and studio of the Finnish-American designer Eliel Saarinen—Cranbrook’s first resident architect and the Art Academy’s first president and the head of the Architecture Department—and Loja Saarinen—the Academy’s first head of the Weaving Department and director of Studio Loja Saarinen.

Meeting room of Dirk Denison Architects, with works by Tadashi Kawamata, Ellsworth Kelly and Aron Gent.

CGN: It sounds like Detroit offered you so much inspiration. How did you come to Chicago?

DD: Chicago has been, for me, not only practice, but also teaching. I’m a professor at IIT, the College of Architecture, and also very involved with the Art Institute through the Society for Contemporary Art and through art, architecture and design departments. Early on at the MCA, there was something called the New Group, which was sort of my introduction to the cultural and collecting community in Chicago. Many of those collectors I met are still our closest friends.

I came to study architecture at IIT where I teach now. In the eighties there was a lot of fluctuation going on in the world of design, and IIT had a very, very strong program. So even though I had come from the University of Michigan–I studied there and then I went and did my Master’s at Harvard–I came back to Chicago because it has always been a city that had a real commitment to placemaking and to innovation and to thinking about what the next generation of architecture was going to be. It’s just a great place to work, and I’ve been fortunate to work all over the country. Chicago is a base that has allowed me that opportunity.

Bucktown residence. Chicago, IL. A renovation and addition whose material, form, and proportion follow those of the original postmodern structure, a sculptor’s studio designed by Harry Weese for his daughter and son-in-law; set back onto an unusual site, it maintains an existing, generous garden.

CGN: Where did you keep art in your mind while you were studying architecture and first becoming an architect?

DD: For me the whole richness of the creative world is part of thinking about place and space making–furniture, design, tapestries, all of the mediums, from painting to sculpture. I’ve always made spaces that are about creating opportunity for those other voices. It’s not just my voice. I’ve never espoused a Frank Lloyd Wright approach, where I design everything. I actually want there to be diversity and I want there to be other voices that I’m in conversation with, because that’s the way I live, and that’s the way I want my clients to make their space. I design for opportunity. With my clients, I can help them build a collection, but obviously many of them have collections before I work with them. They choose to work with me because they know I appreciate how art enriches your life. Sometimes we plan around very specific works of art. Sometimes we plan around very specific commissions working with particular artists. Other times it’s a sense that there will be a moment or a place that is going to be asking for a work of art.

A team member works by a painting by Judy Ledgerwood

CGN: Do you personally have an art collection that is separate from what’s installed in your offices, or does your collection just exist where there is space?

DD: Well, it’s interesting. Our offices have been in the West Loop for 20 years, in this heavy timber building. The size of the space, the ceiling heights and the size of the walls was the first time that I had wall space this scale. My first painting before we even moved into the office was this quatrefoil painting by Judy Ledgerwood that I saw in her studio when I had took a client there to pick something out for their new home. I said, ‘Would you hold that for me? In the next year I’m going to be moving into new offices where I’ll have a wall finally big enough for an eight-foot square painting.’ It’s been somewhat of an opportunity for us, since the idea of having art in the office is that it’s how we design space, and I want my amazing creative team to work in that same environment. Many architects have photographs of their former projects and awards up on the wall. I said to myself, that’s not necessarily inspirational for the team that’s working on whatever they’re focused on. Why not have them learn and be inspired by these other creative voices? So that’s why there is art in the office.

We do switch the art out back and forth between home and work and [my partner] David’s studio as well. About a year ago we had a flood in our apartment, so we were forced to redo it. And as a result of that, we changed our whole philosophy at home, which is where we have just one work of art on each wall. And so as a result of that, we switched things out. We brought some of the bigger things from the office and took the smaller things out of the apartment. So it’s very fluid and we want to change things around. Nothing has a permanent place in how we live with it. The interesting thing is too, because of the artists, I’ve picked up on my parents’ philosophy that most of the artists in our collection are artists that we know, or as we get interested in them, we make a point of getting to know them. And that comes into not only our personal life and our friendships, but also into the office. So if you walked into my office now and talked to someone working there who’s fairly new out of school, they would know who Judy Ledgerwood is. They know there is a person behind the art that they work with.

Office view. On wall: Ad Reinhard’s ’Ten Screenprints’

CGN: Have you had challenging situations trying to blend works of art or a collection into a space you’re designing?

DD: Yes. I think the main thing about working on a collection–whether it’s clients who have never collected art before or long-time collectors–we’re working together. I spend this concerted amount of time in the beginning showing them different lines of thinking about medium or scale or geographic source for works of art. It may be a color story, or it may just be space specific, but it’s something I like them to get to the point of saying, okay, this is what will be fun for us to work on. Obviously I can do the primary selection of the art, but hopefully they’ll get the [collecting] bug because there are many more spaces that they’ll be able to place art in, so I hope they keep looking at art themselves and finding opportunities. Often I will create some specific spaces, like for a glass collection or a wall that’s about ceramics or something so that they can keep thinking as they travel and make their life intertwined with collecting art and living with art. But it’s also the story behind every work of art that is what makes us collectors.

I didn’t answer your question about the difficult works. I have had a couple of moments when someone bought something on a trip for something. One of my clients laughs about this fountain they bought in Morocco. We were starting the project and they were like, ‘We have this fountain. We’d love to find a spot for it!’ It didn’t end up making it into the home. We laugh about it now because we still have that thing sitting in the garage in a box, but they finally realized that there is some sort of line of thinking that does tie everything together. It’s really about things that speak well to each other. I just created a home with a wonderful Spencer Finch that was this very bright fluorescent light with amazing geometry. It was very eye catching, but it worked with the larger aesthetic of what they were doing.

CGN: It sounds like you try to spend a lot of time having those client conversations leading up to when you get started designing that maybe prevent some of those clashes.

DD: It’s another part of the process. I think when it is a couple, it’s important that they are both part of the decision and invested in it. It’s answering both their desires and needs for what we design in what they’ll live in. I feel the same thing with the art, where I really encourage them to make the decisions together and not buy one piece that one of them loves and the other one isn’t fond of. I’ve always approached that with my design work, that if you’re not in love with this option, let’s find the next thing that you are.

moniquemeloche gallery. Chicago, IL. The transformation of a hidden industrial building in Chicago’s West Town into a flexible space for encountering multiple forms of art.

CGN: With regard to commercial spaces, you have designed many gallery spaces in Chicago. What are your main considerations when approaching that kind of design need versus another office or residence?

DD: When you’re doing a space that’s specifically for art–a gallery or an exhibition space–you of course are not designing for particular works of art. Maybe a particular medium, but not specific works. In fact, you want it to be quite the opposite, quite flexible. My general attitude towards spaces for art is to create variety so that there is a sequence of experiences and spaces as well as the clarity of the wall, so that it doesn’t compete with what is going to be brought in, which you don’t know what it’s going to be in the future. So really simple detailing, ubiquitous materials, a flooring material, simple white walls, with maybe the exception of an entry moment or an office moment or something like that. And then lighting, of course, is the most important.

You want to always over-light a space for art and have lighting from more than one source so that you can both throw light on the whole space as well as on highlights. And then you make it all flexible. You make it all controllable so that you have that moment where you want to pin light for a particular work, or you want to flood for something that’s a wall mural. And I think that a lot of times you’ll see space that’s been overly dramatized and that’s fine for a particular effect, but if it’s not flexible, if it’s not dimmable or expandable, it’s too restricting.

I love to bring in natural light, but also moments where direct sunlight will work like a sundial to come in and make its way through a space is more flexible in a home or office than it is in a gallery.

CGN: What’s design moment stands out for you?

DD: Those are really difficult questions because my mind always goes to whatever we’re working on right now. My process tends to make things challenging. In other words, I’m looking for the constraints. I’m looking for the sort of requirements that will make the project better. And that’s fundamentally coming from how it’s going to be used, where it is, what we’re working with. I think what’s so important now is the clear attitude to working with what we have, using existing structures before tearing them down and building something new. More than half my work is restoration, preservation, adaptive reuse. The project that I did just two years ago at IIT, which is three towers that we made from staff into student housing, I actually won a competition at the school for a new 480 bed dorm. I convinced them we had these three legacy Mies van der Rohe designed buildings from the ‘50s on campus that we should do first before we build anything new. That ended up being very successful and has been an amazing opportunity for the students to live in these buildings. And economically, it was significantly less expensive to work with the existing structures than to build something new and of course, much more sustainable and much more environmental.

CGN: Would you like to add anything else?

DD: Even though I am often steering the boat or keeping it moving forward, I see design as having many voices, all of the expertises, all the vantage points. There isn’t just the the client, there are also the contractors, my amazing team of consultants and engineers, everybody at the office. The biggest challenge is listening to all that information, and then sorting out the priorities.

#