Jacqueline Surdell: An Artist’s Voice Helps Scale Her Art

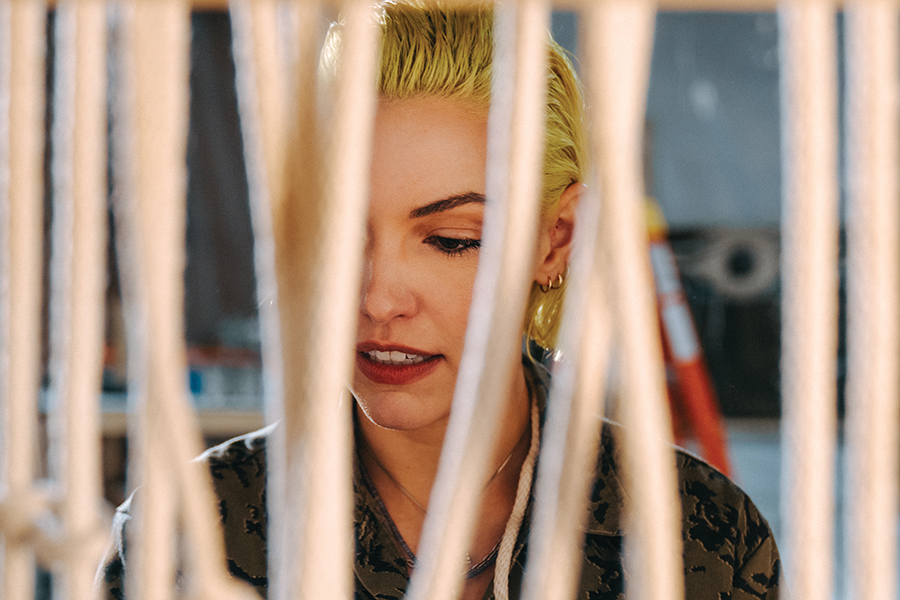

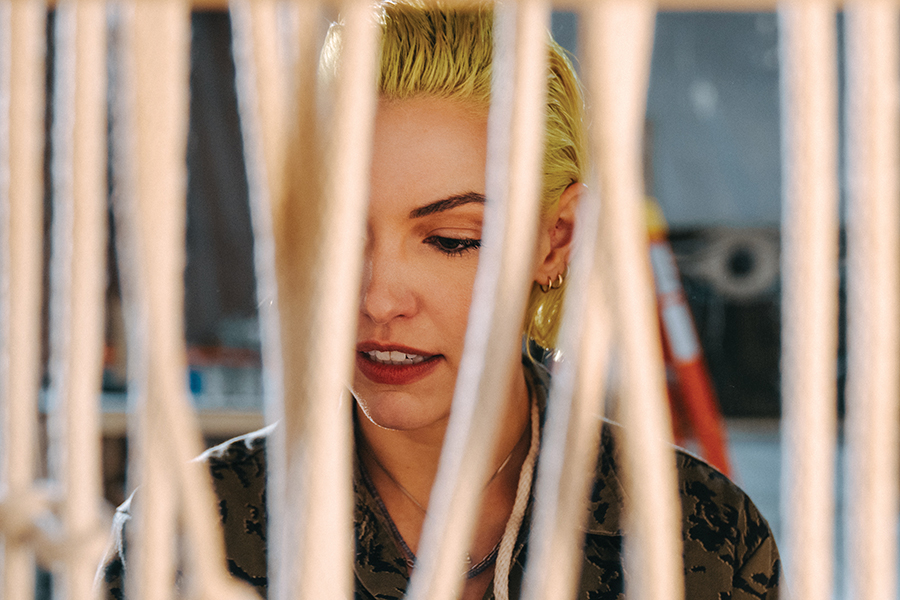

Jacqueline Surdell. Photo by Dayson Emanuel Roa

Note: This interview is featured on the cover of CGN's Fall 2025 magazine. Click here to purchase a print copy and support CGN's work.

By ALISON REILLY

I spoke with Jacqueline Surdell in June as she was preparing for her first solo exhibition at Secrist | Beach, which opens on September 19. Surdell’s large-scale, vibrating tapestries showcase her physical discipline, ambitious vision, and influences from both the Dutch and Polish-Catholic sides of her family. In high school and college, Surdell played competitive volleyball, and her training as an athlete has informed her work just as much as her experience as a painter. We discussed how she became an artist, how she found and sharpened her artistic voice, and how she developed her process for creating monumental, woven work.

CGN: Did you grow up making art?

Jacqueline Surdell: Yes and no. My grandmother is a landscape painter and artist. She’s Dutch, kind of an austere older woman, and she had a studio in her home. I thought it was this really magical place. I had undiagnosed ADHD and issues with reading, and I was really frustrated a lot of the time. She would make me make art with her. It was just something that we did together to bridge generational gaps. Going to museums together, she would challenge me on my random opinions, and so I think in some ways it was more about us having a relationship. She always told me, “You’re my reborn older soul.”

CGN: What was her studio like?

JS: It was so cool. After World War II, she moved with my opa to Toronto, then to Chicago, and then they opened an inn in Beaufort, South Carolina. They had this classic A-frame home on the marsh. It was a very different place from Chicago and really anywhere else in America or the world. The studio was up on the second floor in the corner. It had this really beautiful gray stone flooring and a beautiful skylight, and it was full of treasures. She was very much a collector. When I saw Lenore Tawney’s studio set up at Kohler [Arts Center], it reminded me a lot of my oma’s studio—bird’s nests, shark’s teeth, landscape paintings, other people’s art and photos, beautiful handwritten letters in cursive. I actually used to sleep in there.

View of works in progress by Jacqueline Surdell. Photo by Dayson Emanuel Roa

CGN: You studied at Occidental and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. How did you get there? When did you decide that you wanted to be an artist?

JS: I always found a lot of value in painting. I was a portrait painter, and for me it was more about relationships. I had these really great high school teachers—Ms. Holloway and Mr. Harris. Russell Harris is a photorealism painter who works on the South Side of Chicago. He was one of my mentors, and the way he approached painting was very methodical.

I was a volleyball player, and that was where I was successful. As a student who was otherwise struggling and very shy, I could be wild and crazy on the court, and I also felt that way in the studio. Not really wild and crazy, but I could let go. I played year-round competitive volleyball. I like to say I’m a 0 to 100 person. My mom says, “She’s one track Jack.” Once I decide I’m doing something, there’s no stopping me, I’m like a juggernaut down a hill. That was definitely the case with both art and volleyball.

I went to college and played volleyball but had a horrible time with a new coach. She was really problematic, and we were investigated by the NCAA. It was really absurd, but it was very interesting to see this other side of sports—the reality of power dynamics and what it means to be at a school, which is really a business. It was interesting to learn that the hard way at 18.

Sophomore year I was injured, and I was like “I hate this, I’m not going to play volleyball anymore.” I was also coming into my own as a student. I really loved learning and being good at school versus before I was very much going through the motions to get to volleyball practice. I was always a painter but then I went into sculpture, and I had this amazing professor, Mary Beth Heffernan, and she suggested, “Why don’t you use your physicality to work in the studio?” I thought that was a really good idea. Basically, I transferred it over. I have this very vivid memory of calling my dad and telling him, “I’m gonna be an art major, and I want to be an artist.” And he said, “Okay, we’ll support you. I know whatever you set your mind to, you’ll do it full force.”

View of a work in progress by Jacqueline Surdell. Photo by Dayson Emanuel Roa

CGN: Did you take time off before you went to SAIC? How did you decide to do the next step with graduate school?

JS: I didn’t take time. I wish I did. And I was told to by everyone. To be honest, I had no concept of what it meant to be an artist. I would sit in Mary Beth’s office and ask her questions like, “What does it mean to be an artist?” Because for me it was always this Sunday painter hobby. The double-edged sword of having it so close with my grandmother was that it was something that I loved and saw all this value in, but I think my family perceived it as this nice thing that my oma also does, versus taking it seriously. I’d been in school my whole life. I clearly needed structure. She [Mary Beth] told me, “Get a studio, just get a studio and work.” And I was like, “What does that mean? I’ve been coached and taught my entire life. I don’t have my own voice.”

I remember going to SAIC and the first day we were asked to present some of our work. Everyone’s work was so impressive, but what was more impressive was that everyone could talk about why they were making stuff. I was sitting there thinking, I don’t know why I made this. I can make up some shit, if you really want me to. I was also struggling with performance anxiety and wanting to sincerely and authentically and honestly talk about the work and not really knowing where it was coming from. It’s hard to have a sense of identity when you’re coming out of school and put on the mask your whole life of everything’s good, everything’s fine. Especially for volleyball—you put everything to the side when you get to the gym, which can be helpful if you know that you’re doing that. But if you don’t know that you’re doing that, you can forget who you are.

Self discovery was a large part of my grad school experience. I did a lot of video and performance and came out of it making really different work, but it was always connected to textiles and fiber. It was more finding the conceptual framework even if it was more identity-based because that’s always made more sense to me.

CGN: Do you feel like you have that voice now?

JS: Yes, I feel very confident in why I make the work and what it says. At the same time I do find myself separating the physicality of the work and the mental side of things. I do that on purpose, because it is so labor intensive. I’ve seen athletes talk about this, too, especially like football or contact sports where you have to enter into this sense of life or death. Don’t talk to me after a game, I’m not myself necessarily. I’m a goblin, a studio gremlin right now. I can’t be eloquent right now. I’m still honing my voice and trying to figure out exactly what that means. I would always say in volleyball, “I put my body where my mouth is—I’ll show you how hard I work.” My oma taught me, “Here’s art so you can express yourself, you don’t have to speak.” Not in a shut up way, but there are other means of expression that I found. That physicality or expressing myself through work is part of the voice. It’s a big part of it for me.

CGN: What is a typical day in your studio like?

JS: When I’m setting up, I’m building looms, ordering all these materials, trying to make sure I’m going to get all the packages in time, laying out the plastic, cleaning everything. And then once I’m set up, it kind of looks like a shit show in there, but basically I can stand in one place and reach everything I need. It might look crazy, but for me, it’s the perfect amount of controlled chaos. I usually get there around one or two p.m. and then work until midnight.

My studio is a big space, and it’s so nice to have it separated from my home, which is the opposite of what I had before. I can really focus and be very present. Before, my bed was upstairs and I would go downstairs and the work would be there. And I find them very sentient, so I feel like they would call to me, they’d say, “I’m not done.” Or I’d have some idea in the middle of the night, and I would just go do it downstairs and cut something apart. It’s three in the morning, and I’m like, “What am I doing?”

Above: Jacqueline Surdell, Suddenly, she was hell-bent and ravenous (after Giotto), 2024. Nylon cord, steel, polyester fabric, steel spool top, steel chain and meat hooks. 65 (body) x 252 (pole to pole) x 7 inches. Below: Detail of Suddenly, she was hell-bent and ravenous (after Giotto).

CGN: How did you start working on such a large scale? Is it monumental? They feel monumental to me.

JS: I did make a monumental one. They feel really big. It’s funny, actually, the small ones are very difficult for me to make. I remember Daniel Quiles [Associate Professor, SAIC] was in my studio a couple of years ago, and he said, “How do you make sure it’s not just a bunch of material?” Sometimes with the smaller ones, it does lack that sense of close and distant space. The larger ones can enter into a landscape conversation because of that scale.

The first one I ever made was at Occidental, and it was a five by five foot piece, because I was painting on the other side of the canvas. I was looking at the weave of the canvas, and it was not happening, the painting was not good, and I could not figure it out. I knew I wanted to do something in landscape, but I didn’t know exactly what I was trying to say. Even just physically, it didn’t feel good or look good. I was looking at the grid of the canvas, thinking about why L.A. highways look the way they do and what a grid in a city means. I had never thought about Chicago being on a grid and then suddenly thinking everything is on a grid. Looking at Anni Albers and those kinds of artists and conversations around the grid from a weaving perspective. I flipped the canvas over, and I made a peg loom on the other side. The grid’s a really strong structure, and I thought I can evolve this, make it bigger.

Last year Carrie Secrist opened a new space, Secrist | Beach, on Hubbard and asked me to make an in situ work for a survey exhibition, Making Time. That’s when I made this 30 by 20 foot piece, because I had the capacity to do so. I’ve always felt like a goldfish. I will grow to the size of space.

CGN: What are you working on right now, and what projects do you have coming up for this fall?

JS: My solo show at Secrist | Beach opens September 19th, and we are also doing a solo booth at the Armory Show the first weekend of September.

CGN: For your solo show, do you have a theme?

JS: I’m exploring landscape painting. I’m interested in landscapes as objects, but also thinking about them as the places that you live in and the romanticism of a painting versus actual nature. Britton Bertran [Director, Secrist | Beach] and I have been talking lot about, there’s this Latin phrase, “Natura Non Constristatur,” and it means something like nature doesn’t give a fuck about you. Natura Non Constristatur is the title of my co-curated group exhibition, opening alongside my solo presentation at Secrist | Beach on September 19th. I’ve asked a lot of questions about landscape and thinking about the forest as witness. Especially with these horrible times we’re in and this personal upheaval I’ve had this last year, who is witnessing that and what is the psychology of the forest of our mind—trauma and growth and entropy, something that’s dead that comes back to life. What is our capacity to hold or to be open, to change and to rest? Each piece is sort of an episode of a long HBO show. They’re like little movies for me, little stories, each one has their own narrative, a theme within the theme, if you will.

CGN: Do you sketch before you start? You talked about getting the materials all set up, but before you get there, how are you mapping out your work?

JS: It depends on the piece usually, but they start honestly with a lot of Photoshop collages. A lot of times there’s woven fabric in these pieces, and they’re printed paintings or photographs that have to do with this narrative that I’ve ascribed to the piece itself, its identity. Sometimes the image is clear, and sometimes it’s obfuscated, it’s more about the color or the gesture at the end of it. They just need to begin, because there’s so much editing that happens throughout. The small ones actually helped me a lot, because I learned that there is something to this creation, building up of something small and then editing, cutting and taking away and finding new things, opening up negative space and things that couldn’t have been there without it being underneath something else, like a reveal or findings, a sense of discovery.

A lot of it is just the labor of getting started, which is again the loom process, and then there’s this period once they’re well on their way, well formed, on the loom, and I take them off the loom, and it’s this very dramatic thing. They’re hundreds of pounds, dangerous, and we’re all like ahh! Things go everywhere. Then I string a pole through the top and hang it, usually with the help of two or three people, and then see how the tension or lack of tension changes the forms. I re-approach [the work] and make more photographs, collages, and sketches. I’ve been sketching a lot of bark and trees that might not necessarily be seen in the pieces themselves, but it’s helpful for me to just think through where I want them to go—how landscapes speak through absence.

Jacqueline Surdell, Golden shroud (golden fleece), 2024

CGN: I read about your grandfather who worked in steel mills on the South Side of Chicago. Can you talk about your relationship with him and how that plays into your work?

JS: My dad is Catholic-Polish and grew up on the South Side of Chicago in a neighborhood called Hegewisch. Hegewisch has the highest Polish people per capita outside of Poland. It’s right on the border of Indiana. There’s no gas station there, because people just go to Indiana. I was raised Catholic, I’m confirmed in the church and all that. Church was the first place I ever experienced irreverence and where I asked why can’t a woman be a priest? The amazing pagan-ness of Catholicism. It’s gaudy and so over the top. A lot of the teachings end up being like, you just work really hard and respect your boss, and God will take care of you if you’re a disciplined person. That was part of how I grew up, and that’s part of my work.

My jaja [Polish side of the family] was in Korea and then came back and worked in the steel mills. He fell once from a scaffolding, and he shattered one of his legs. He had these steel pins, this crazy contraption, a steel pole on the outside of his leg and then rods that came from the pole into his bones, so they could reset it. I remember thinking as a child, ‘Oh that’s the steel that you made. Steel broke you, so steel will fix you.’ He thought that was really funny. He was very smart even though he didn’t graduate high school. He was very aware of that and embarrassed almost, like he felt couldn’t contribute to my adult life. Catholicism was my connection with him. I remember our last conversation was this massive fight. And then he passed away in 2016. It was so sad.

[Then] when my busha [Polish side of the family] passed away in 2022, I had built up a resistance to Catholicism and religion in my life. When [both grandparents] were gone, I was like what is my identity? Do I actually not believe in this? What does it mean to have a belief that’s just against someone else’s? That’s why I made this piece, I’ve been calling it Suddenly, it’s that monumental piece I was talking about.

Jacqueline Surdell in the studio. 2025. Photo by Dayson Emanuel Roa.

CGN: Do you feel like your work has changed since then?

JS: I think the way I’m approaching things is very different, but I don’t know if the physical work has changed. The physical work really changed during the pandemic. I really thought we were all going to die. That was my other moment where I was like, fuck it, I’m just gonna do this. I’m gonna make art full time. This is the only thing that makes sense to me. This is what I can contribute.

For a long time, I felt like it was very selfish to be an artist and to work all day in your studio and be alone–I’ve been rethinking that approach as well, what it means to be a community member. But being a little more honest has opened up spaces for friends of mine or family to say, [for example,] “You doing what you want is very inspiring to me. It makes me feel like I didn’t have to stay in law school. I could be a therapist [or anything else] if I wanted to be.” I was so honored and surprised by that. I do think there’s something to be said about honoring your truth, knowing where you fit, and being okay with that. Be okay with how it’s never going to be perfect.

#

Jacqueline Surdell will be exhibiting with Secrist | beach at the Armory Show at booth 216 at The Javits Center, New York | September 4–7, 2025.

On view in Chicago at Secrist | Beach:

JACQUELINE SURDELL | THE CONVERSION: RINGS, RUPTURE,

AND THE FOREST ARCHIVE, September 19–November 15, 2025

The artist is also co-curating a concurrent group show at secrist | Beach, Natura Non Constristatur

View More information and works at jacquelinesurdell.com • Instagram @jacquelinesurdell

and secristbeach.com