Recapturing an Indiana Art Center: A Visit to Newfields

Newfields IMA, Photo by Eric Lubrick; Courtesy of Newfields

By BIANCA BOVA

For those attuned to the dramas of the art world, Newfields needs no introduction. Formerly the Indianapolis Museum of Art (founded 1883), the institution reconceptualized itself in 2017, marrying the museum to its grounds and surrounding attractions in Indianapolis, Indiana. Newfields became the unified name for the 152-acre compound that houses the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Fairbanks Park, The Garden, Lilly House, and the Elder Greenhouse. It then further extended its brand to the Miller House and Garden in Columbus, Indiana.

The rollout of this expansion and rebranding was less than smooth. It was deemed by critics to be “the greatest travesty in the art world,” and earned Newfields’ then-director Charles Venable the honorific of “the most controversial museum director in America.” The museum was accused of abandoning its mission, and Venable of turning “a grand encyclopedic museum into a cheap Midwestern boardwalk.”

Venable resigned from his role as Director in 2021, though not officially because of the backlash from his refocusing of the museum’s program. Rather, it was a decision born of the fallout from a racially insensitive job posting. All of this left Newfields seemingly adrift, and the institution cycled through an astonishing three leaders in just four years. Today it is helmed by Director Belinda Tate and President and CEO Le Monte Booker, whose efforts to right the ship are legible.

Its museum is one that I know better than most. I was born and reared in Indiana, and I come from a family of automotive professionals and enthusiasts. All my life we made regular trips from my hometown of St. John down to Indianapolis to attend events at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. These trips invariably included visits to the Indianapolis Museum of Art as well. The IMA looms as large in my memory, and went as far in forming my interest–and eventually my taste–in art as did the Art Institute of Chicago.

Roy Lichtenstein (American, b.1923–d.1997)

Five Brushstrokes, 2012; Design Date 1983-84

painted aluminum

480 x 77 x 15 in. (assembled)

Courtesy of the Robert L. and Marjorie J. Mann Fund, Partial Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation

Still, I never felt compelled to visit Newfields. I met every headline regarding its dysfunction with fresh disappointment. Earlier this year I was given good reason to reconsider my position, when a checklist for one of their current exhibitions The Message is the Medium landed in my inbox. There isn’t really a museum I wouldn’t go to for a show with a roster that reads in part as follows: Vito Acconci, Robert Irwin, Donald Judd, Anselm Kiefer, Robert Rauschenberg, Do Ho Suh, Rachel Whiteread, Richard Hunt, Roger Brown, Robert Smithson, Lynda Benglis, Simone Leigh, James Turrell. So I booked a trip to Indianapolis and went to Newfields, ready to be impressed by the exhibition and resentful of the degradation of its environs.

Vito Acconci (American, b.1940 - d.2017)

Round Trip (A Space to Fall Back On), 1975; rebuilt 1987

Medium and Support: stools, boxes, audio tape Dimensions: Dimensions variable

The exhibition itself is not without curiosities that are suggestive of ongoing administrative troubles (no one, including the exhibition’s curator, could pin down an end date for the show or explain to me why it seems to be in the middle of an indefinite run). Setting that aside, it is an exceptional exhibition. Vito Acconci’s Round Trip (A Space to Fall Back On) and James Turrell’s Acton are both early masterworks requiring participatory attention that alone makes a visit worthwhile. Robert Rauschenberg’s Sling-shots lit #3, one of the few pieces from a series that utilizes sailcloth, mylar, and moveable window shade systems to remain in public circulation, as well as Anselm Kiefer’s Die Himmelspaläste (The Palaces of Heaven), are proof positive of the deep collecting habits of a handful of notable benefactors to the museum, as well as the commitment of the museum’s Contemporary Art Society (which for 58 years acquired work for the permanent collection, until being dissolved in 2020, along with the rest of Newfields’ affiliate organizations). The show is rounded out by a suite of loans (the aforementioned Smithson, Leigh, and Benglis sculptures) from Art Bridges, the partner loan network of Crystal Bridges. It's of interest to see this initiative put into practice, and the works lent make a fine complement to the museum’s contemporary holdings.

Simone Leigh (American, b. 1967)

Las Meninas II, 2019

Medium and Support: terracotta, steel, raffia, and porcelein

Dimensions: 71 1/2 x 77 1/2 x 62 in.

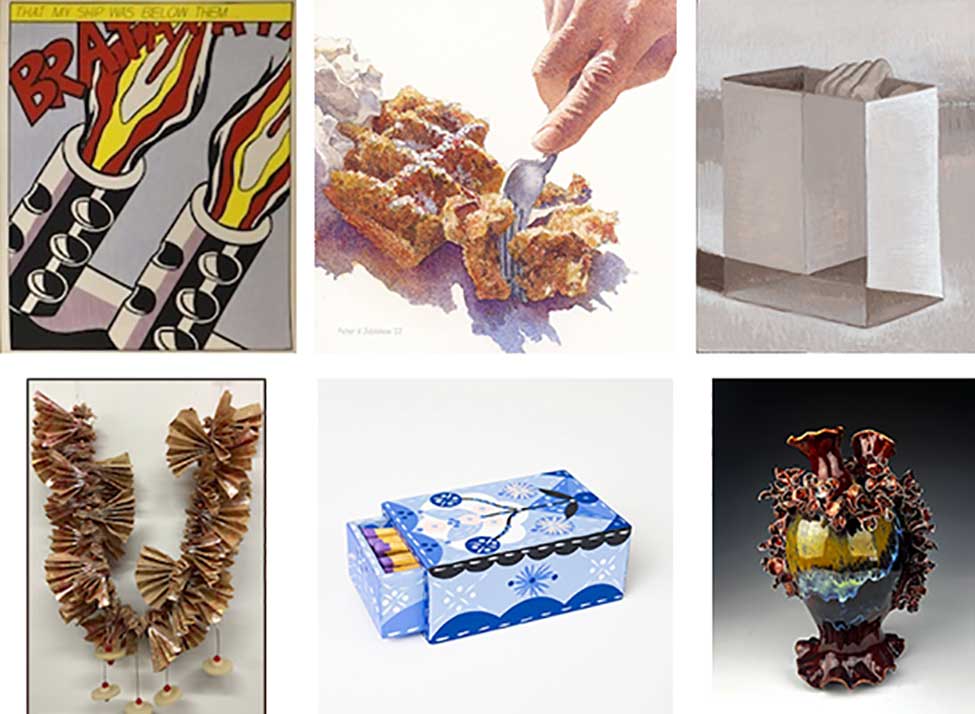

Beyond the contemporary galleries are equally satisfying exhibitions drawn from the museum’s extensive American Art, Asian Art, European Art, African Art, Native Art of the Americas, Textile and Fashion, Design, and Glass collections (the lattermost being especially robust, as it's a regionally significant medium). Periodically the galleries are punctuated by interdepartmental installations that veer from the heavy-handed (a Jenny Holzer LED sign hung alongside a 15th century Italian wedding chest sidepanel) to the smart and striking (paintings by Joan Mitchell and Sam Gilliam flanking a set of Frederick Wilson Tiffany stained glass windows depicting the Angel of the Resurrection). Also of note is the museum’s atrium, which houses one of only a handful of large-scale, site-specific institutional commissions by the late light and space artist Robert Irwin. Light and Space III spans the rise of the escalators servicing the museum’s four floors, lending the space an ethereal, heady, almost spiritual atmosphere. By way of special exhibitions on view, the Robertson-Slapak Collection of Chicago Imagist works puts to shame any other retrospective of the group’s output mounted in the past decade, and speaks to what feels like an oft-overlooked Midwestern collector class that has pockets as deep and taste as good as any propping up the more well-known institutions in larger cities.

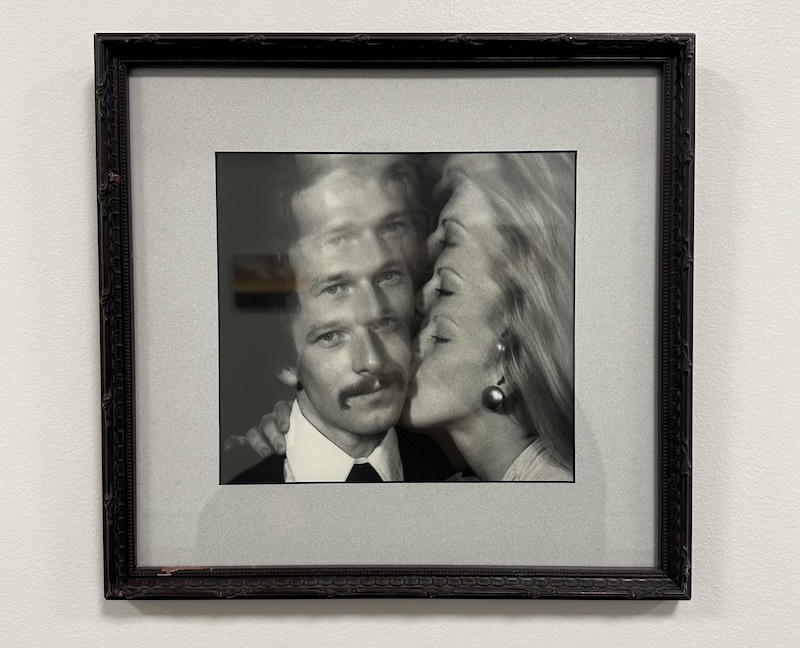

Kathryn Janeway, Michael, 1978

Down in the museum’s lower level, alongside the theatre and the giftshop, one finds galleries presently devoted to the 93rd Annual Juried Exhibition of The Indiana Artists Club and a show, Artists Among Us, of works by Newfields’ staff. One work included in the latter, a 1978 photograph entitled Michael, by Kathryn Janeway (a member of the museum’s security team, who shared with me that she had not previously exhibited her work), is nothing short of exceptional. I continue to think about it daily, which I can't say about much other work I’ve seen recently. Both exhibitions feel like throwbacks to a time when institutions on the whole were more in touch with and respectful of their core constituencies–which is to say, those engaged directly with the art world, rather than the general public at large–and were as much a pleasure as a surprise to see.

All told, Newfields should be on the shortlist of museums that are in and of themselves a worthwhile destination. May (when I went) happens to be an ideal time to travel to Indianapolis, as the city is energized by the lead-up to the “greatest spectacle in racing,” the Indianapolis 500, which is run every Memorial Day weekend. Moreover, there is not a more hypnotically beautiful place to be in the Spring than Indiana, and not a nicer place to experience the full pleasure of it than, quite honestly, on the grounds of Newfields. A long stroll through the manicured English gardens and rolling prairies that surround the historic Lilly House (itself a beautifully restored example of turn-of-the-century architecture) can replace all that a long, hard Midwestern winter depletes from one.

In the aggregate all of this is almost–almost–enough to make one forget that Newfields is simultaneously responsible for propagating such cultural dreck as Funky Bones, various immersive projection rooms, and of course the infamous Cat Video Festival that seemed, with its debut, to signal the beginning of the end.

All museums in all strata of the cultural sector are beleaguered by problems of one kind or another. It is inherent to their very nature, their bureaucratic form. Newfields has perhaps brought more problems onto itself than other institutions, and surely has borne them more publicly than most. For all of this, at the core still sits one of the great American museum collections, which in fairness ought to be a point of pride in the Midwest, for its content if not its delivery in concept. Still and all, the message–as we’re told–is the medium.

Support for this article’s research was furnished by a Travel Grant for Visual Arts Journalism from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.

#