Northwestern’s Block Museum Reopens

BY FRANCK MERCURIO

Last August, the staff of the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University were confronted with a near disaster. A pipe connected to the museum’s sprinkler system burst. Luckily, the collections were not damaged; but the museum needed to close its gallery spaces—for all of fall quarter—while repairs were made.

Instead of viewing the closure as a set-back, the Block saw an opportunity to upgrade its facilities and focus its energies on developing a robust series of programs and exhibitions for winter quarter. “It really gave us a chance to do what we needed on a system wide level to bring us to a state-of-the-art space,” said Susy Bielak, the Block’s Associate Director of Engagement. “It also gave us time to launch with a program in January that we’re really quite exhilarated about.”

The museum’s under-utilized entry-foyer has been transformed into the Spot Lounge, a more inviting—and activated—space. Comfortable seating, study areas, and WiFi now attract students, professors, and university staff to this new social hub.

The Block’s renovated gallery spaces will be celebrated officially on Saturday, January 18, with the unveiling of two new temporary exhibitions and a slate of public programs.

Steichen/Warhol: Picturing Fame features photographs by Edward Steichen (1879-1973) alongside Polaroids by Andy Warhol. It is the first exhibition to compare the works of the two artists side-by-side and to fully explore the influence of Steichen’s photography on Warhol’s portraits.

“The exhibition posits an unlikely comparison between Steichen’s early glamour photography and Warhol’s late career portraits,” says the Block’s Special Projects Curator, Elliot Reichert, who organized the exhibition.

Beginning in the late 1920s, Steichen became famous for photographing Hollywood’s elite and defining the conventions of glamour photography during Hollywood’s golden era.

Steichen/Warhol presents vintage Steichen prints from the Block’s permanent collection (recently donated by Richard and Jackie Hollander), including portraits of film stars such as Greta Garbo and Clara Bow.

These images had a profound effect on Warhol, influencing his silk-screen style portrait paintings of the 1970s and 80s. Warhol began his process by snapping Polaroids of celebrities and wealthy collectors, consciously employing some of the same photographic conventions established by Steichen 50 years earlier.

“Warhol never really intended these [Polaroids] as art objects to be exhibited,” says Reichert, “They are pieces of his process that have been reintroduced as objects worthy of study.”

The exhibition presents a range of Warhol Polaroids recently acquired from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, bringing a fascinating new perspective on the artist’s creative process. Combined with 49 Steichen images, the total number of works in the exhibition is 140.

Opening in tandem with Steichen/Warhol is The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929–1940, curated by Northwestern University PhD candidates John Murphy and Jill Bugajski. The show examines Depression-era artists who questioned the capitalist system in the face of economic catastrophe and practiced art as a form of social and political activism.

“Artists were becoming activists, taking it to the streets, beyond the galleries and museums,” says Murphy, “and asking ‘What kind of art earns the name revolutionary?’ They saw themselves as soldiers in a class struggle using art as a weapon.”

“Artists were becoming activists, taking it to the streets, beyond the galleries and museums,” says Murphy, “and asking ‘What kind of art earns the name revolutionary?’ They saw themselves as soldiers in a class struggle using art as a weapon.”

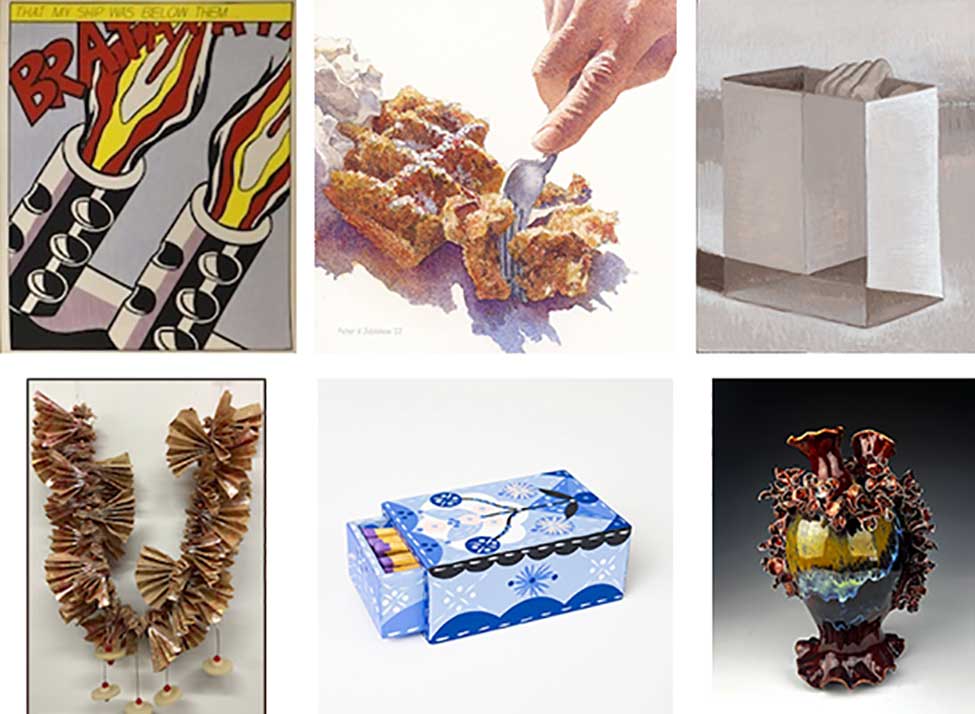

Examples in the show include over 100 prints, paintings, posters, rare books and ephemera assembled from the Block’s permanent collections, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Terra Foundation, the Smart Museum, and the Hull-House Museum.

In the 1930s, printmaking was seen as a way of distributing art to the masses. Lithographs, etchings, and woodcuts—by the likes of Carl Hoeckner, Rockwell Kent and Stuart Davis—figure prominently in the exhibition.

“These artists were making political gestures,” says Bugajski, “but also trying to shift the social fabric by moving art away from institutions and the upper crust and bringing it to the people as a force for change.”

The Block will open The Left Front with a series of events and programs meant to engage Chicago in the question of “What is revolutionary art?” On Saturday, January 18, the museum will host what Bielak calls a “multi-fold opening” including performances by NU students and a presentation on “Fashion and Revolution” by Tom Mitchell, professor of English and Art History at the University of Chicago. For a full roster of upcoming programs addressing “revolutionary art,” visit the Block’s website at block.northwestern.edu