Crossing Borders: Practicing Medicine and Art

BY MEGAN BONKE

Science or Art? Left brain or right brain? It actually takes both sides of our brain to perform complex tasks like math, art, science, and writing, and sometimes it can be helpful to remember that being creative and logical are not mutually exclusive.

With this year’s Chicago Artist’s Month theme, Crossing Borders, in mind, I spoke to two Northwestern medical students who just started their second year, who have personally embraced art and consider their professional lives better because of it. One appreciates the break art provides from the usual grueling medical school schedule. The other sees opportunities for new approaches to high-stakes problem solving. Frank Borrows double majored in Biology and Physics and minored in Chemistry at the University of Virginia and is currently obtaining a duel MD/PHD degree. Blake Platt received a Bachelor’s in Chemistry from John’s Hopkins and aspires to become a surgeon. - MB

When did you first begin a regular art practice and why? How often do you practice art?

Frank Barrows: I remember painting or drawing all the time as a little kid. When playing the Game of Life, I would always try and be the artist, but I would also try and have the highest wage. Now, during the school year, on the weekend immediately following exams, I paint.

Blake Platt: At the beginning of school last year, I needed a hobby. I played baseball in college, but since then I’ve had a sort of void. I have always wished I could draw, and one day I decided to try. Once I started I had a lot of fun, so I just kept at it. Now, after I finish studying every night I pick out something to sketch or paint and fiddle around with it for about an hour before I go to bed.

How would you describe your work?

FB: Wonky. Where I feel confident, I like messing with perspective. In actuality I’ll have some drinks, get kind of messed up and just paint into the night instead of studying sometimes.

BP: What I have painted is what I would mostly describe as slightly abstract, sometimes geometric landscapes. I just really like water and color.

Do creativity and art help you in medical school?

FB: Since I started painting again, my life is better in general. Art is completely stress free for me. Painting is where I get to be productive and creative and not just sit and watch Netflix, but also not study.

BP: Absolutely. You can tell when we were studying anatomy because I drew all of these [sketches] and copied them from Frank Netters. Anatomy is a lot of visualization, especially with muscles - they have a three-dimensional place in the body, as well as a Latin name that’s confusing, and an origin, insertion, and action with relation to bones. I spent a lot of time sketching body parts from cadavers, and that really helped me.

What are some of the struggles of being a medical student, and does art supply any form of relief?

FB: The lack of flexibility we have in our lives while in medical school can be depressing. We sell our souls in hopes of becoming a doctor. Art helps, since I don’t ever want to be strictly defined as a medical student, which can be difficult while in medical school.

BP: The larger picture of medicine is very much about problem solving, but I find that the first two years of medical school are very much about learning, then applying that knowledge to a situation, then regurgitating it on a test. We can get a one track mind and end up losing focus. Exercising a different part of our cognitive ability helps us see more.

Northwestern UNIVERSITY Medical School requires a humanities program that requires three hours one day a week for one month for one semester a year. Tell me your experiences with this program.

FB: We would visit the Art Institute and walk around with an ex-Pathologist who was really into art. I remember we were supposed to examine a detail in art to transfer it to a detail in medical school. I was able to see a lot more than I would have on my own.

BP: We sculpted facial muscles onto a skull with clay. The woman who taught us teaches plastic surgeons how to sculpt ears and other body parts. It gives a broader sense of community - physicians are working with the human body, and so are artists, so is everyone. The program exposes you to something that you wouldn’t necessarily do, and you find a part of yourself that you didn’t know. I didn’t know that I would enjoy this, but I love it.

Any final thoughts on art and medicine for yourselves?

FB: As a medical student everything we do is critiqued so hard, and you have to set really high standards for yourself. I think I really enjoy making art because I’m such a novice. So little is expected of me; I get recognition just for trying. That’s really refreshing. Painting and artwork are so deep and rich, and I get a whole new world to explore in a completely pressure free environment, which is exhilarating.

BP: It’s a well-known fact that doctors don’t wash their hands as much as they should. Since the 1900’s, everyone who has tried zealously to change this has died insane and poor because they have been shunned from the medical community. Recently, the Royal London Hospital commissioned members of the Royal College of Art to ask why the doctors were not washing their hands enough. The designers walked in and said that of course no one is washing their hands enough; everything is filthy. The furniture was designed in a way that was difficult to clean. Say I wash my hands and I take care of a patient and I go type; then I have to wash my hands again. If you are taking together and putting apart an engine, you’re not going to wash your hands after every bolt, but that’s essentially what doctors have to do. Now the hospital has commissioned this school to design furniture that is easy to clean and does not collect as much dust and dirt. It’s still early, but it seems to have a lot of success. This is what I was talking about when I said we can get one-track minded. You can lose a sense of what the problems are where you only see a concept of the problem, and then someone comes in and says, “Of course this is wrong. This is terrible, and this is very easy to fix.”

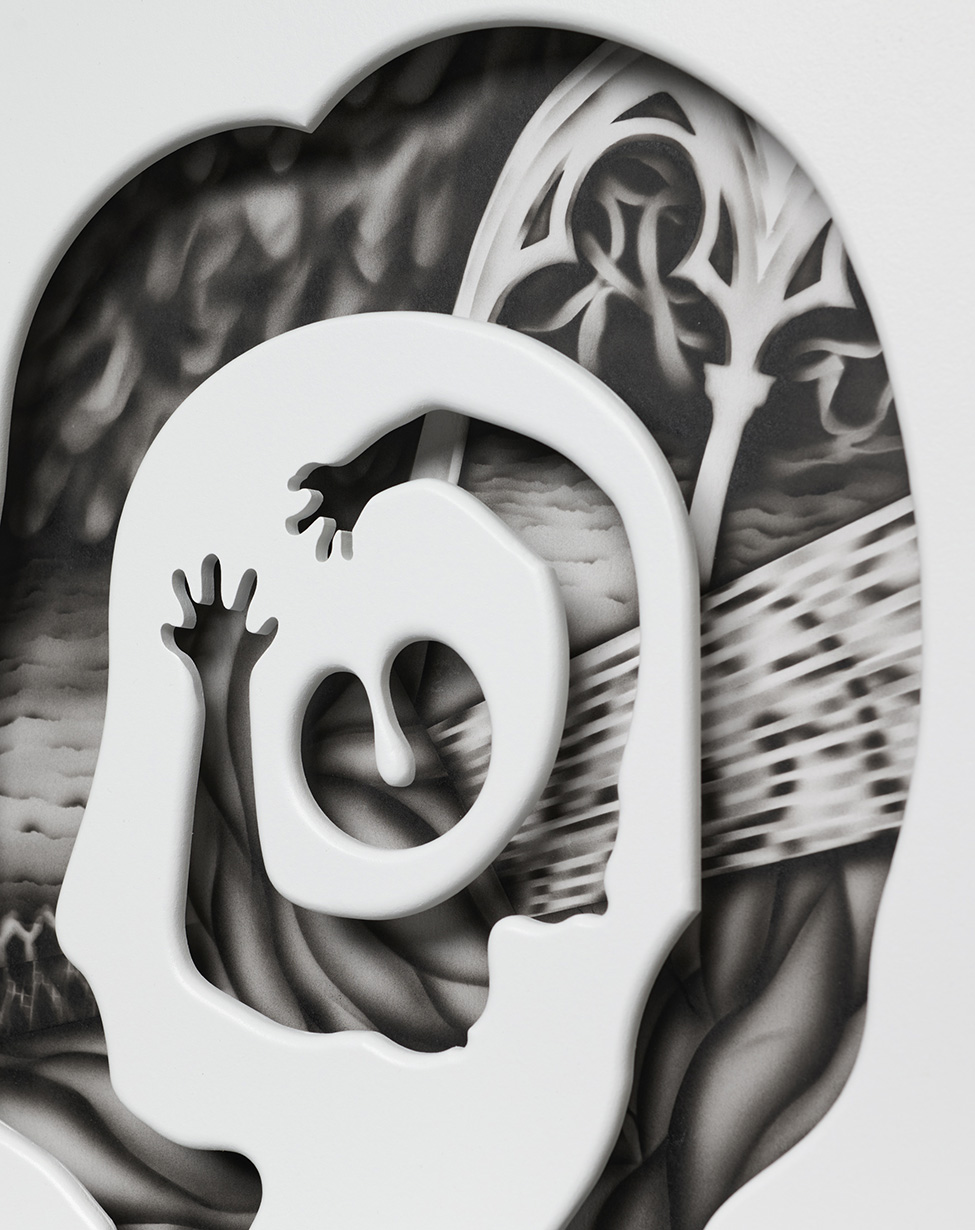

Top Image: Blake Platt, Excerpt from Sketchbook, 2014