As Fairs Dominate, the Gallery Changes

By FRANCK MERCURIO

Like all commercial ventures, the buying and selling of art has its risks. Economic flux, changing tastes, and new ways of doing business—such as Internet marketing and sales—present challenges and opportunities for art dealers. Perhaps the greatest challenge in recent years has been the rise of the international art fair. With more gallery owners compelled to participate in an increasing number of fairs, the relevancy of the traditional art gallery model is being questioned. Some gallery owners have opted to trade-in their physical spaces for private “by appointment only” consultancies. (Russell Bowman, Kasia Kay, and Aron Packer provide some recent examples in Chicago.) Yet other gallerists have found innovative ways of keeping their gallery spaces active, despite the financial pressures of art fairs and the sometimes attendance-killing effects of online marketing and social media.

In interviewing a number of past and present gallery owners, one sentiment is universal: the art fairs are important for generating business, but they often strain finances. The entry fees can be prohibitive, especially for the big fairs, such as New York’s Armory Show, Art Basel Miami, and EXPO Chicago. But to compete in a global art market, participation in fairs is essential, if for no other reason than to capture the attention of collectors.

“All the fairs are expensive, but it’s an expense that we build into our budgets because they are necessary,” explained Monique Meloche, owner of Monique Meloche Gallery in Wicker Park.

Meloche founded her gallery in 2000, and since then she has participated in many art fairs, both in the United States and abroad. Her background as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art informs her curatorial approach to both gallery exhibitions and the gallery’s presence at art fairs.

“It’s important to do what we do at the gallery, and it’s important to do what we do at the fairs,” said Meloche.

“I treat [the art fair booths] as exhibitions, and ask ‘how is this going to be strategic for the artist?’”

During the run of the 2016 Armory Show, Meloche tried a new approach. Instead of participating in the fair itself, she rented a storefront for seven days on Rivington Street around the corner from the New Museum. The pop-up gallery featured the works of Sanford Biggers and Ebony G. Patterson. This experiment proved to be a less-expensive alternative to a booth at the Armory Show, yet it still brought in capacity crowds and made sales—and allowed the artwork to be presented in a more curatorial atmosphere, apart from the blatant commodification of the fair.

“It worked for us because for the last four years we were in New York [during the Armory Show] with a booth,” explained Meloche. “This year, people looked for us in a different place. The Lower East Side, as a location, was really convenient for people to visit.”

Newer galleries in Chicago are also finding innovative ways to participate in major art fairs. In 2015, The Mission teamed up with Andrew Rafacz Gallery to share a booth at EXPO Chicago. The partnership not only reduced expenses, but it also provided a kind of synergy between the two programs.

“We’ve been collaborating with Andrew Rafacz [at EXPO] for the past two years; and that’s been really successful,” said Sebastian Campos, owner and principal of The Mission. “Our programs align well. We’ve discussed venturing out to do some regional fairs together and seeing how that works.”

Founded in 2010 and located in a storefront previously occupied by Shane Campbell in West Town, The Mission contains two exhibition spaces on its first floor and a third in the basement. On it’s website, the gallery bills The Sub-Mission as “an alternative installation project space dedicated to the development of artists living and working in Chicago.”

“Using the basement space as a non-commercial space was probably the smartest thing we’ve done for the gallery,” explains Campos. “We bring in artists that we probably would not have known about otherwise.”

A committee of local arts professionals selects the artists and projects that appear in The Sub-Mission. (Currently, Samantha Bittman, Eric May, Matt Morris, and Teresa Silva serve on the committee.) The program allows for unconventional and experimental work to be displayed in the gallery, often in dialogue with the more commercial work exhibited on the first floor.

“The amount of diversity that we display there echoes what we do in the main space,” said Campos. “It’s also a way of giving back to the art community; it provides another outlet for artists who are living and working in Chicago.”

The Sub-Mission is just one example of how gallerists are thinking creatively about how to bring more people into their spaces. But even gallery owners who are now without physical spaces are exhibiting work in unexpected ways.

Both Aron Packer and Kasia Kay closed their respective galleries in 2015 for different personal and professional reasons; but both saw the need for “changing up” their businesses and exploring new ways of engaging with the art market through a combination of consulting, private sales, and special projects.

“I did shows for 14 years straight with a two or three week break each August like everybody else,” said Packer, the previous owner of Packer Schopf Gallery. “So part of the reason—stopping after 14 years running my space—is, I think you need to change things to stay fresh.”

Since closing his gallery, Packer has embarked on Aron Packer Projects, consulting for Lillstreet Art Center. He also organizes pop-up exhibitions featuring his artists at venues such as Evanston’s Space 900 and Co-Prosperity Sphere in Bridgeport. These shows are a new way of keeping his artists in the public eye.

Similarly, Kay, the owner and founder of Kasia Kay Art Projects, still sees the relevance of displaying artwork in public spaces, despite closing her own gallery space, Kasia Kay Gallery, in 2015. She’s experimenting with pop-up exhibitions in established retail spaces, including high-end boutiques like élu in Lincoln Park.

“I’m very selective in where I show the work,” said Kay. “It has to be somewhere sleek and very modern, where I can envision similar clientele.”

The advantage of partnerships with like-minded venues is that Kay can collaborate on cross-marketing and cross-promotion. It also allows her to introduce artists to new audiences.

“I’ve always enjoyed promoting young, upcoming artists,” said Kay. “I’m looking for new ways that I can promote again. I’m going back to ‘art project mode’ where I started.”

The art market is always evolving. The frenzied art fair landscape, along with a fluctuating economy and a changing collector base continue to motivate both gallery owners and private dealers to create new ways of displaying artwork, promoting artists, and bringing art to the public.

Franck Mercurio is a writer and curator based in Chicago. mercurio-exhibits.com

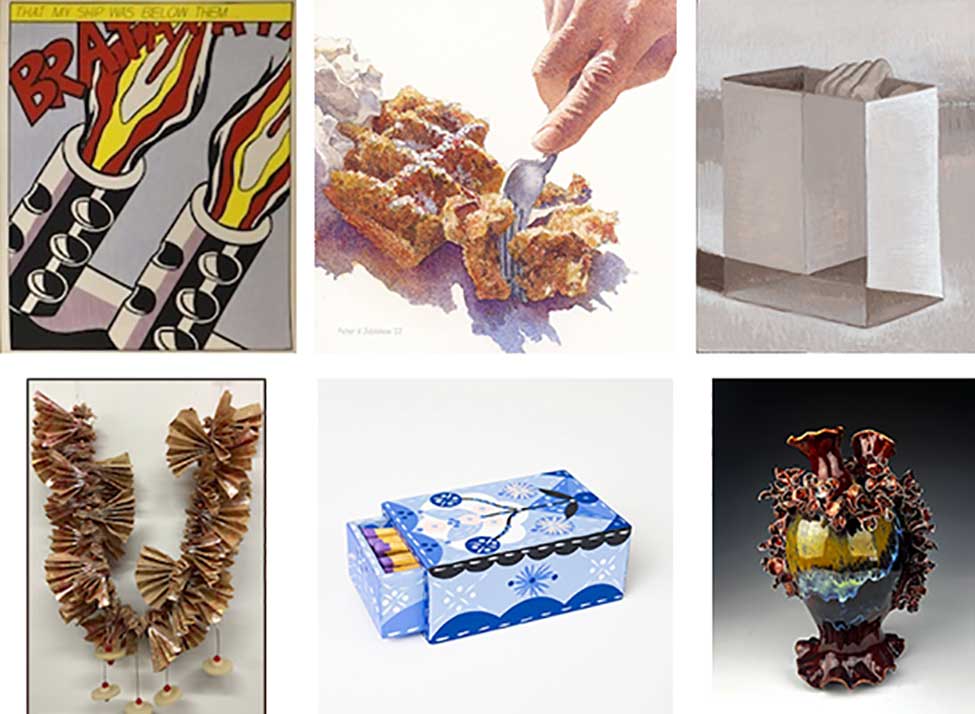

Pictured at the top: An overhead view of EXPO Chicago, 2015 at Navy Pier