The Personal Art of Collecting

A CHICAGO IMAGISTS COLLECTION SPANS TWO CITIES

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

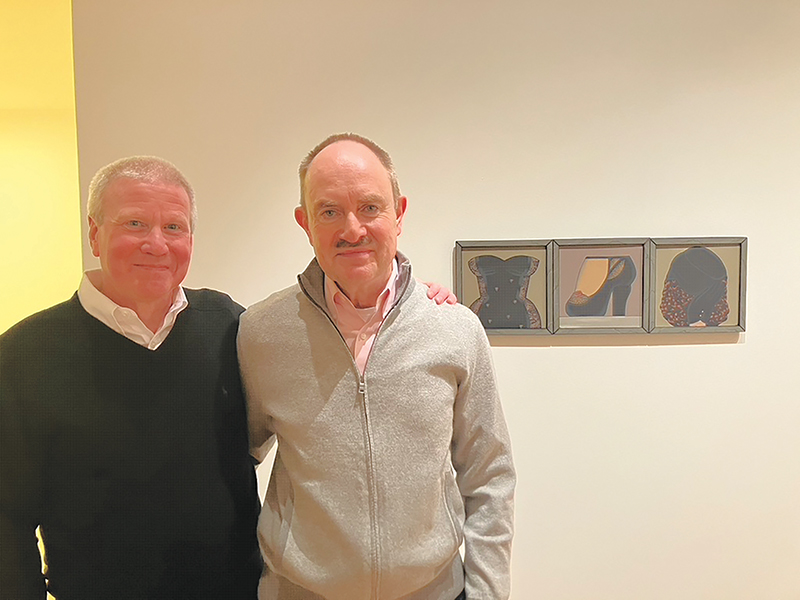

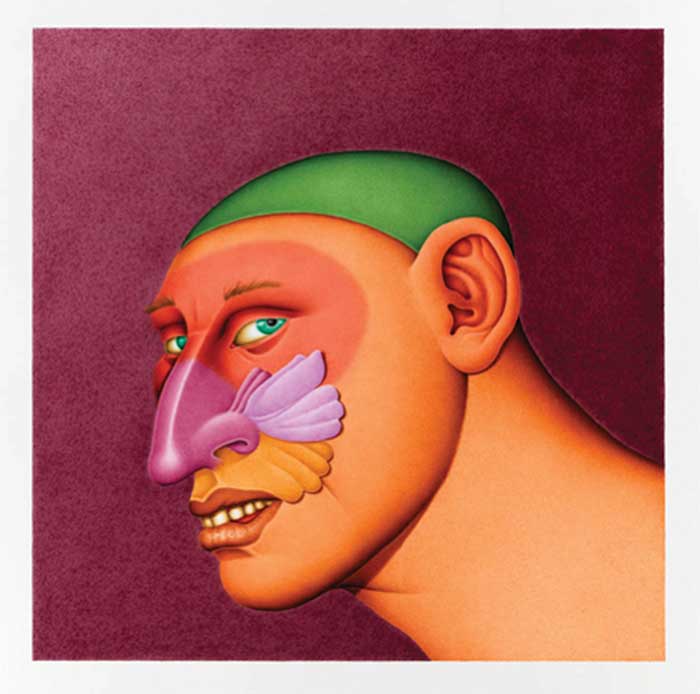

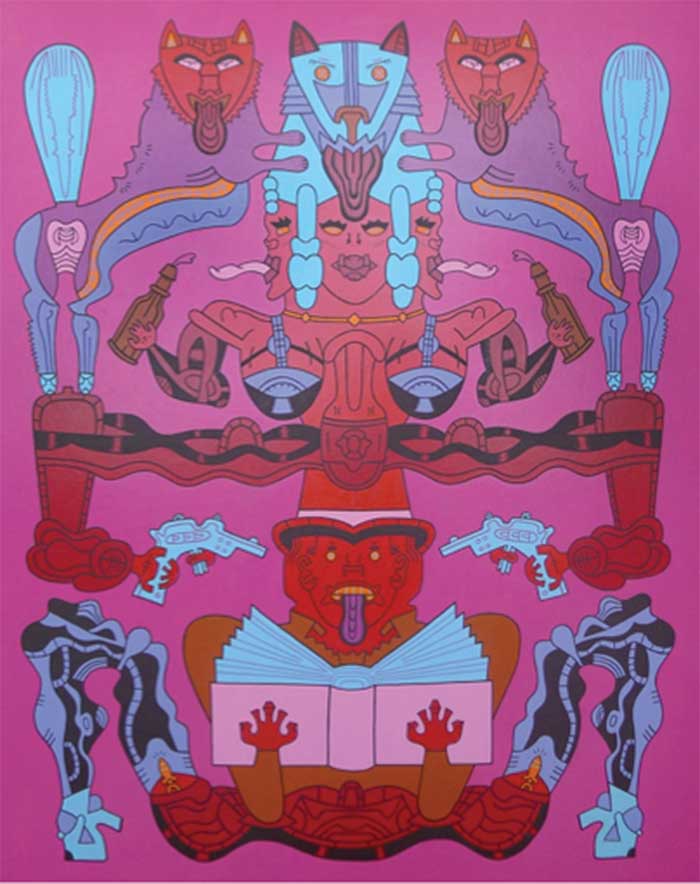

Christopher Slapak and Michael Robertson’s shared passion for contemporary art began decades before they would start to build a collection of work by Chicago Imagists and other related artists. At the University of Chicago in the 1980s, the two met when they were medical students in the same class. When a colleague in the University’s Masters of Fine Arts program recommended that they see a show of famed Chicago Imagist Ed Paschke’s work at the Renaissance Society in 1982, they went as two poor medical students who didn’t know what to expect. What they saw blew them away; looking back now, they say if they’d had any money they would have bought the whole show.

After that experience, they became increasingly interested in the Imagists, a group of representational artists who banded together in the 1960s, learning about figures such as Roger Brown and seeing shows at the Hyde Park Art Center. At the time, their lives were dominated by their medical education. A love for art was in the background, but they did not think they would ever collect art. They didn’t know what a gateway that Ren show would ultimately be to weekends packed with gallery visits and two art-filled homes.

When Christopher and Michael finished medical school at UChicago, as well as their internships and residencies in Chicago, they moved to Boston to continue their medical training. Contemporary art was not a focus for the pair during nine years in Boston.

They returned to the Midwest when Christopher was recruited to work at Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis, and Michael was offered a position at the Indiana University School of Medicine. After a decade in Indiana, around 2005, they made the decision to purchase a condo in downtown Chicago, so they could visit on weekends and enjoy all that the city has to offer. Living in a contemporary high rise was a contrast to their traditional, 100-year old, antiques-filled home in Indianapolis. The time was right, with a new base in Chicago, to begin exploring the contemporary art scene again.

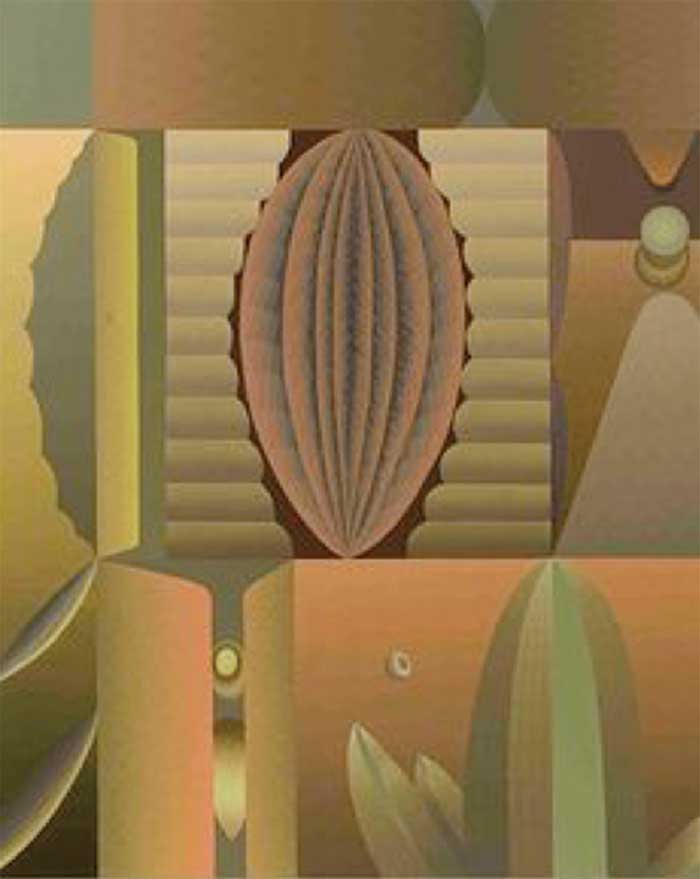

Michael and Christopher met Chicago dealers Ann and Roy Boyd early on in their reacquaintance with the art community. The Boyds’ gallery had been in business for over 30 years, and their program’s focus fit well with Christopher and Michael’s taste for vibrant, unique works by living artists, such as William Conger and Brigitte Riesebrodt. The four quickly became good friends, with Ann and Roy introducing them to many artists and showing them a range of works. A focus on unique art that was abstract, rather than representational, defined their early collecting.

The couple also enjoyed supporting living Chicago artists. Explains Christopher, “We want to support the artists who are working now, because if they’re deceased you’re just supporting the person that owns the piece, not the artist. We came to appreciate that half of what you’re paying for goes to the artist.” From Michael’s perspective, “It was an ethical thing, we just thought it would be better buying the work of living artists in this area and supporting them – we love Chicago.”

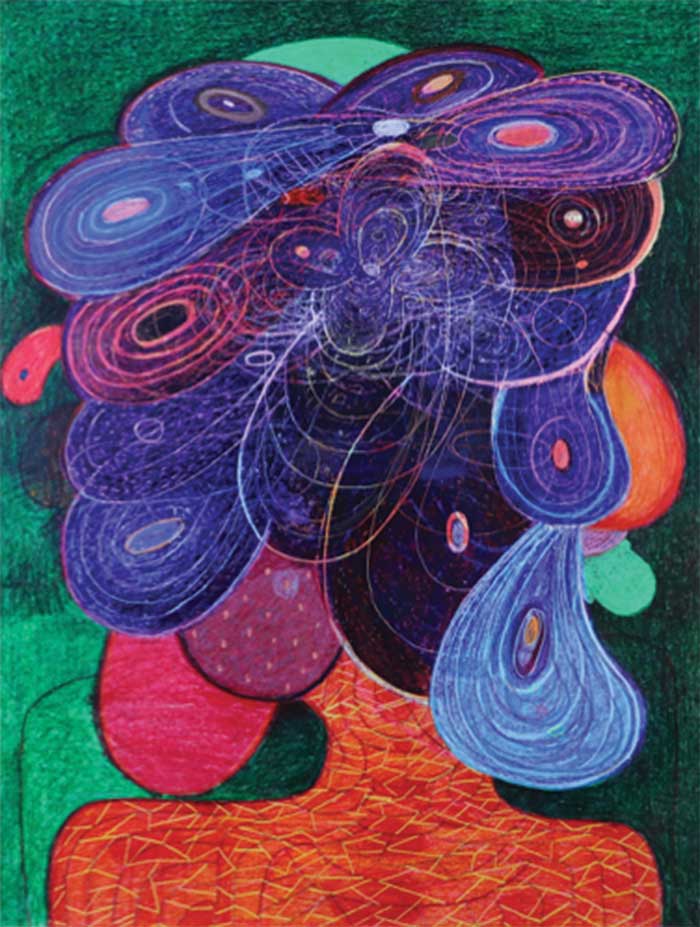

What began as a somewhat casual desire to buy art while also supporting local artists quickly became more serious and sophisticated. Michael recalls, “That was the ironic thing. I said, ‘Oh, it will take us years to find anything we like,’ and of course that was not the problem, no, not at all.” Christopher adds, “There was a handful of artists we quickly started collecting: Rebecca Shore, William Conger, Brigitte [Riesebrodt], and John Phillips. Those artists led to an exploration of more up and coming contemporary artists, such as Geoffrey Todd Smith, Dana Degiulio, Molly Zuckerman-Hartung, and Matthew Metzger. Before they knew it, they had started to define and build a collection.

When Michael and Christopher moved back to Chicago in 2005, they were eager to return to the galleries and take in all that was happening in the contemporary world. They immersed themselves, often going to as many as 25 galleries in a day. They visited dealers, met artists and attended opening receptions. By looking at so much, the focus of their collection shifted radically.

Christopher says, “When an artist had caught our eye, we would explore a little bit more and get to know who they were.” Michael adds that though they did do their research, it was mostly hands on, spending entire weekends in town going from gallery to gallery. When they would travel to other cities gallery hopping was their starting point. Christopher notes, “My business takes me to New York a lot, so we also started going to the Chelsea and Upper East Side galleries to get an understanding of the full breadth, as much as we possibly could.” Michael and Christopher each confess they just like seeing what’s there each time they visit. One difference they’ve noticed when traveling, according to Michael, “In Chelsea they rarely talk to you, but they do in LA and San Francisco. And Chicago.”

They each feel at home in galleries and have done the majority of their exploration and buying through dealers, but according to Christopher, a key collecting moment presented itself at Art Chicago in 2006, the same year the longstanding art fair unexpectedly moved to the Merchandise Mart. “When we went to our first fair, we were overwhelmed.” Michael concurs, “There was so much stuff to see, it was a sensory overload.”

Chicago dealer Russell Bowman had a booth at Art Chicago that year, and that was where Christopher and Michael first met him. Bowman was showing BG Summer, a work by Ed Paschke from 1991, which sent the couple right back to that 1980s exhibition at the Renaissance Society. Christopher recalls, “We both remembered how much we really loved him, and when we saw this piece at the fair – it was more money than I thought we would ever pay for a piece of art, but we’d always wanted a Paschke – we bought it.”

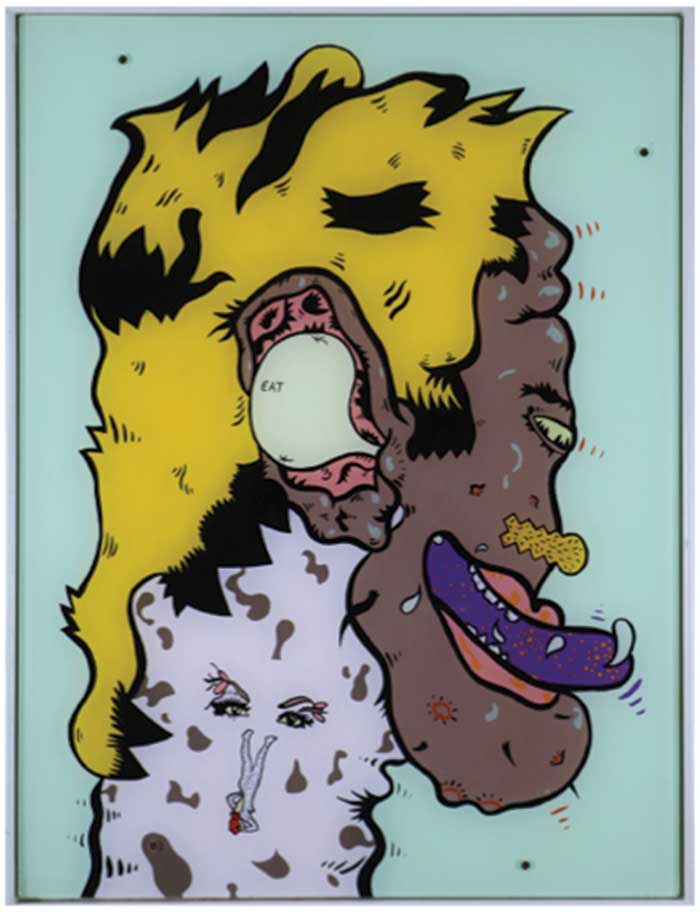

For the next couple of years they were satisfied, as they admired the Paschke on weekends in their Chicago condo. Like a tempting sweet that they couldn’t resist forever, they eventually considered buying other Imagist works. In the mid 2000s, a few paintings by Paschke and Brown were available on the secondary market, but many were still privately held. First, they bought a Roger Brown. Then a work by Karl Wirsum. They continued their research and made inquiries.

The pair got to know local dealers Carl Hammer, Jean Albano and Karen Lennox, and they kept in touch with Bowman, who would call if he had something that he thought might interest them. Once they bought a large Roger Brown, and then a couple more Wirsums, they made the decision that they should find space to display the works at their home in Indianapolis, since the house has a third floor.

Michael admits that whenever he makes a declaration about collecting, usually the opposite will happen. Around 2008, when the national recession was beginning, and with their buying increasing in frequency and expense, Michael said to Christopher, “You know, we will never really put together a serious Imagist collection at this point,” Despite the headwinds that were ravaging collectors in the rest of the art world, Christopher and Michael were in fact inspired to do just that. Christopher reflects, “No one was buying much of anything at that time.” Michael was skeptical, “It was too late – we agreed that all the best works were already in collections and that we would get a few dribs and drabs.”

Christopher figured it was worth attempting anyway, so they reached out to the four Chicago dealers they already knew to let them know that if they had more pieces come up to let them see them. What they began to see struck them as much more remarkable than dribs and drabs. “They started showing us incredible examples coming out of private collections.” Not only was the recession motivating some collectors to sell, but there was also some generational turnover due to collectors who passed things along to heirs who wished to sell what they inherited. To Michael, who wasn’t counting on those scenarios, he figured these prime works would end up in museums. Christopher points to that period as yet another tipping point, “We got a few pieces, and then we got a few really lovely pieces, and then we had to start thinking seriously about actually putting together a Chicago Imagists collection.”

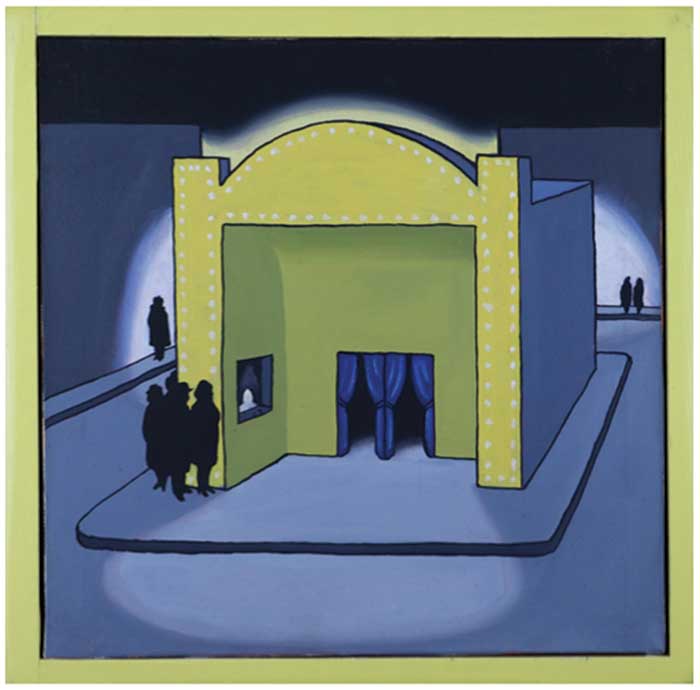

Ironically, the Chicago artists collection is in the couple’s Indianapolis home. The collection prompted a remodel of the second and third floors, and the house’s traditional feel provides a striking setting for contemporary works. In Chicago they ended up displaying an array of contemporary abstract works. John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, of Chicago’s Corbett vs. Dempsey gallery, suggested that the way to stitch the two pieces of the collection together was to think about the abstract painters who were contemporaries of the Imagists. Around 2012 they began to actively buy works from the ‘60s and ‘70s by abstract painters who either worked with the Imagists directly or were clearly influenced by them, including Richard Hull, Jordan Davies and Evelyn Statsinger, who preceded them.

Prior to having a focus for the two parts of the collection, Christopher and Michael would go to a fair or gallery, see something they liked and just buy it. Now, for the most part, they are very disciplined about what they buy and why. There are pieces in the collection that they still love but which they acknowledge they would not buy now. Christopher points to two distinct works in resin by German-born artist Markus Linnenbrink, “We would not likely buy a piece [by Markus] right now because he’s really outside of our collecting focus.”

That discipline has not come at the expense of maintaining relationships with artists living in Chicago. Michael points out that the couple is still buying work by young, up and coming Chicago artists, such as Matthew Metzger and Andrew Holmquist, among others, in an effort to keep up with the contemporary scene, even though much of their focus and resources have gone towards pursuing the Imagists and more historical works. According to Christopher, one artist they have collected in depth is Rebecca Shore. He says they have visited her studio several times and haven’t missed an opening since first buying her work. It was through Shore that the pair was first introduced to Corbett vs. Dempsey, when she moved to the gallery from the now-closed Byron Roche Gallery in River North.

They began collecting with a desire to support living artists, but then they bought their first Paschke after the artist had passed away. They both admit that the rules can change over time, and how you start out is not where you’ll end up. Either way, the contemporary as well as historical relationships all seem to be connected.

More than building a collection or just pursuing elusive works, Michael and Christopher enjoy the experiences that the art world offers. As Christopher sees it, “The diversity of contemporary art is just stunning right now, I mean it can be overwhelming for anyone.” Michael confesses, “We love looking at everything. It’s just interesting to us. It’s challenging. It’s intellectually stimulating. There’s tons of stuff that we would have no interest in collecting – some of the really conceptual work I find fascinating, but I would absolutely not want to live with that in my home. We are drawn to things with a lot of visual interest. We’ve got enough purely intellectual activity in our professional lives, we don’t need that in our art collecting lives.”

Michael and Christopher seem to represent an old fashioned way of doing things in the art world. At a time when so much is experienced virtually or through a screen, both men are passionate about in-person visits to galleries and about relationships with living artists. Michael admits, “I can’t see how people would not go to galleries because, unless you collect videos, it’s an analogue experience. How can you appreciate a Markus Linnenbrink or a Teo Gonzalez through an image? It just doesn’t work; you have to be there to understand the scale and texture – all of it.”

For Christopher, “If you know the artist, maybe you can acquire art from afar. You’ve collected their work before, so you might understand it through an image. I think it’s still best to see it in person.” The couple has bought art sight-unseen via auctions, if something prevents them from travelling to a gallery or auction preview, but ultimately they are adamant that up close is the ideal way. They recommend that anyone trying to get introduced to art should rely heavily on personal visits and not just virtual research. They are hopeful that once people tire of looking at everything on a tiny screen and viewing art only for the selfies, the trend will return to participating in the physical art community.

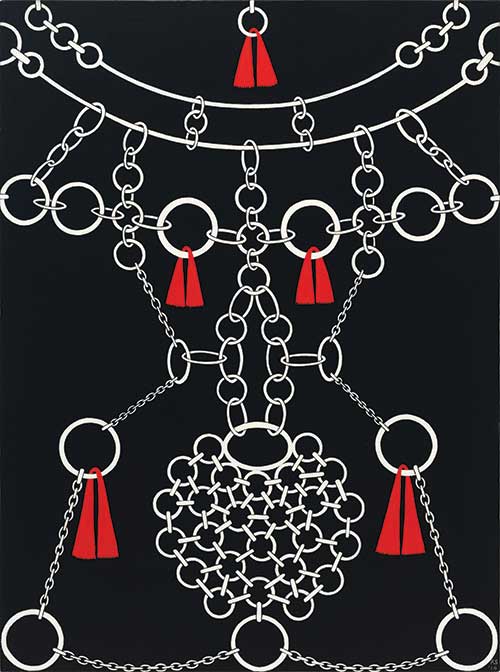

Michael and Christopher seem to be very busy professionally, yet they always find time to go and see art. They will switch roles this summer when they curate a show at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery in River North. Chicago and Indianapolis – What’s the Connection? is a group exhibition (July 14–August 16, 2017) featuring the work of faculty members at the Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis. This exhibition explores common themes and concerns of contemporary artists working in Chicago and Indianapolis. Herron started out like the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where there was a museum collection and then an associated school. Eventually Herron became part of the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis system, and the art collection became the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Today the school is very studio-oriented, devoted to producing working artists. Michael and Christopher had been attending shows at the school for some time, but they did not know much about the academic program. It was William Lieberman who suggested that the couple curate a summer group show at the gallery, and when the subsequent discussions were taking place, the idea took shape to do a faculty show. Michael and Christopher are candid about the fact that they are not curators, and that they have never done something like this before, but they were up for the adventure, and the idea of putting together a gallery show of work they find compelling was appealing. They are also excited for the opportunities it could present to the artists.

Amidst the pressure of assembling a public exhibition for the first time, Christopher and Michael still find themselves doing what they love most – seeing art, visiting studios and talking to artists. The couple continues to hunt for what appeals to them, and their passion for art never dims.