Marcela Torres Wants Us To Experience Violence

By RILEY YAXLEY

The first time I meet Marcela Torres, I make a complete fool of myself. For our interview, we meet at The Clayton, a cigar lounge in the West Loop. I have never been to a cigar lounge and feel overwhelmed following Marcela around the cramped, glass humidor. We stop to let a group of three businessmen squeeze in front of us and, after admitting that I know nothing about the various cigar options, she chooses one for me. We sit at a small, round table in the corner of the lounge and Marcela demonstrates how to properly light a cigar using the matches the host gave us.

“You want to hold it at a little bit of angle,” she says, and takes a drag from hers. I forget to regularly smoke my cigar during the interview, allowing the smoldering embers to die out, and attempt to relight it several times with my dwindling supply of matches. After the fourth or fifth time, Marcela graciously fetches a torch lighter from the host and offers it to me. “Here. This might be easier.”

A colleague invited me to attend Marcela’s second professional cage fight at Joe’s Live in suburban Rosemont in early March. I wasn’t able to make it to her fight, but nonetheless I was introduced to Marcela’s work and was intrigued by her use of martial arts as a way to explore the “mental space of fear” that makes violence possible.

During the past year, I have spent a significant amount of time writing and thinking about whether or not art can affect change, specifically as a way to achieve justice for marginalized communities.

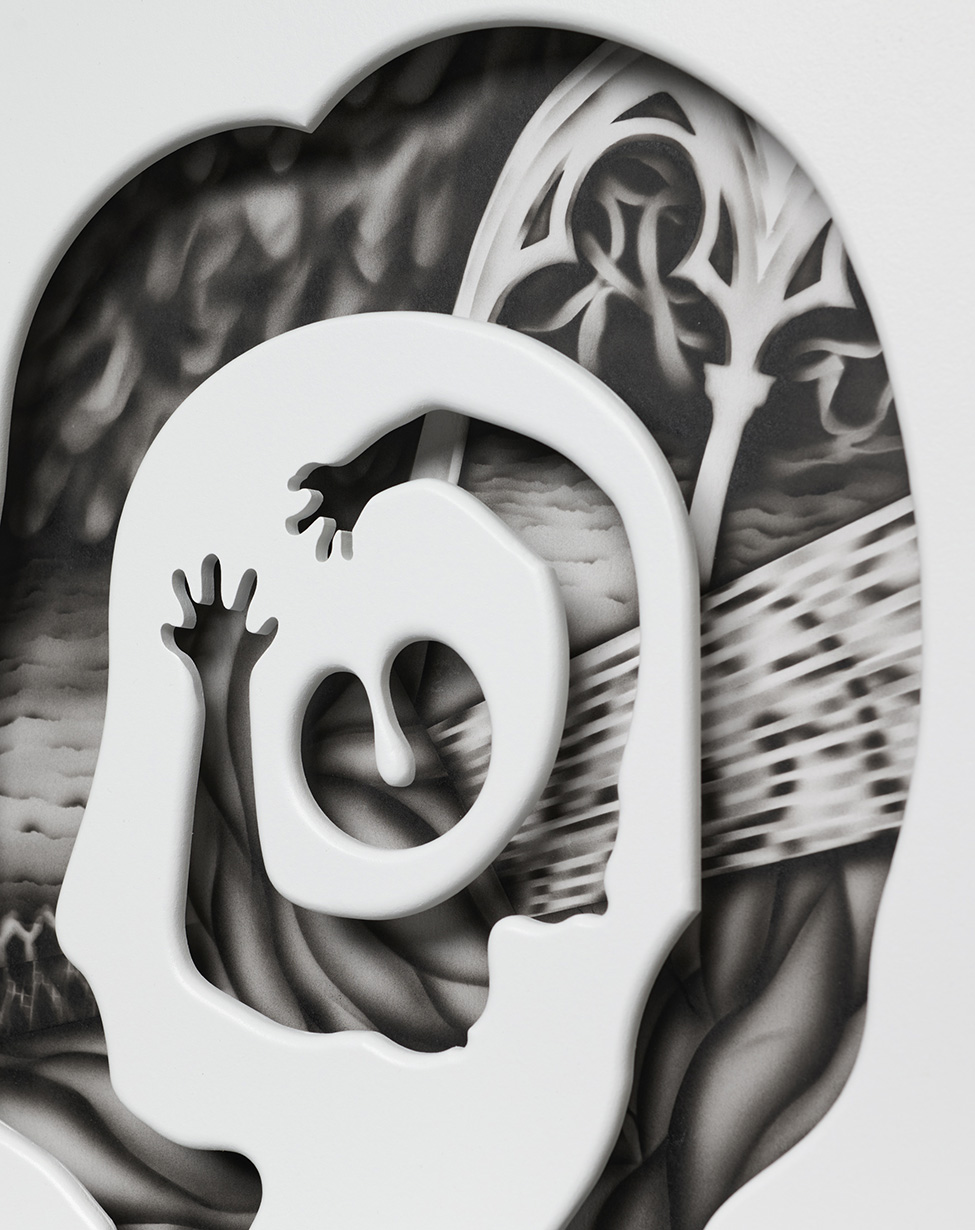

Marcela has been performing Agentic Mode, a 45-minute movement performance incorporating Muay Thai martial arts, literature, and oral history, for the past two years. Most recently, she performed for EXPLODE! Queer dance: Midwest at Northwestern University, and she was scheduled to perform at the Rose Wagner Theater in Salt Lake City and at The Momentary in Arkansas this spring, until the COVID-19 pandemic upended public events for the foreseeable future.

When I ask Marcela about her process of recreating violence in a gallery setting and how she avoids removing violence from its very real contexts, she pauses before cautiously answering, “I do want people to have intense experiences, but I also want it to be a ‘slow consensual experience.’”

Agentic Mode is structured into five segments based on Jeff Cooper’s “Color Codes” of awareness (the code was originally four colors used to describe one’s mindset during a lethal confrontation: white, yellow, orange, and red.)

The “Color Codes” allow her to achieve this gradual, immersive experience, beginning with the white section of the performance, which represents being unaware or inattentive. Here the gallery is brightly lit and Marcela performs a dance that demonstrates elements of Muay Thai form, showing how the martial art can be used for self-defense and as a way to inflict violence. She also reads a series of monologues in between repetitions of the dance, reciting for her audience:

“The combatant was not an isolated individual: his actions were taken on behalf of the nation, a hierarchical military establishment, and an intimate, interdependent platoon—this was what distinguished martial combat from murder...”

During this monologue, Marcela alludes to the title Agentic Mode, exploring how individuals can commit gruesome, horrific acts on behalf of a nation exploiting nationalistic beliefs to trigger them to act in primal self-defense.

Next comes the yellow section – alert, but still relaxed, no immediate threat. The lighting changes. Marcela creates hand symbols and movements referencing guns and fight techniques before the room goes dark for the orange section, where an immediate potential threat is acknowledged.

“I wanted [the audience] to feel a little trapped,” Marcela says about the dramatic lighting change. At this point, viewers are likely feeling unnerved, perhaps a little claustrophobic at just how close they are to the unfolding performance. Marcela begins punching the boxing bags she built herself. They are embedded with microphones and attached to loop and reverb pedals that record and distort each strike to form a cacophonous soundscape that reverberates through the gallery.

The intensity builds as the performance enters the red section, which represents a definitive lethal threat. Marcela, her voice a riotous shout, recites from memory the lyrics of American hip hop duo Mobb Deep’s “Survival of the Fittest.”

“There’s a war goin’ on outside no man is safe from. You could run but you can’t hide forever...”

The use of the song shifts the audience’s attention to how urban communities may often be forced into survival mode to act in different ways. Cooper’s “Color Code” becomes a means of understanding how living in a constant state of fear – whether orange or red –causes people to act with a different code of ethics than other communities living under white or yellow.

Bathed in crimson light, Marcela straddles the vaguely human-shaped body bag, walloping it over and over again. She hits it for as long as she can while the uproarious, looped sounds continue to ricochet throughout the gallery, reaching a deafening crescendo. The room goes black and the sound continues for several moments before disappearing completely. The last section of the performance has begun.

Marcela takes off her tan, desert camo pants and wraps them around the body bag. She cradles it for a minute before crawling towards the crowd, dragging the bag behind her. She rubs her sweaty body against audience members. Some back away, their panicked, repulsed expressions detectable in the dark. Others gently touch her shoulders or back. Eventually, she finds a lap to sit in, asking to use their cell phone as a light so that she can read a final text.

When I ask Marcela about this portion of the performance, she says “meekness or asking for help can be really disgusting to people.” Our instinctive reactions as audience members are revealed. Do we offer assistance or comfort? Do we revile her? Do we look for a way to escape? We have lost control of the situation.

The relentless pace and length of Agentic Mode feels like an exercise in endurance, intended to exhaust both Marcela as well as her audience. However, Marcela adds that the shape of her work has also been determined by career pressures. She jokes she wasn’t getting as much gallery attention earlier in her career, explaining how she realized she needed to make a performance “at least 30–40 minutes to be on the bill by itself.” She adds that there must be objects incorporated as well in order to call it an exhibition.

Marcela is insistent, “I strive for performance to be a really technical machine. I don’t want to be thought of as only a performance artist. I also want to be considered an athlete, a theorist, an educator.” To me, the faint, discolored bruises on her face from the fight a few nights prior remind me that she is challenging herself in a different way than other artists do.

She shyly admits to feeling like an imposter in the fight community that she has borrowed inspiration from and expresses an earnest desire to understand what it means to be a member of that community.

“I lost the fight”, she says sheepishly, adding quickly that it made her realize, “Maybe I’m finally doing the thing I said I was. Having somebody that strong trying to hurt me, I couldn’t fall back on my plans or training. Instead, I used my instincts.” Despite her loss, Marcela explains how terrifying it was to have a person taller and stronger than she more or less attempting to kill her.

“Oh my God, my performance is beating me up,” she says about the experience, laughing. ”But, I asked this person, ‘Please, beat me up.’”

In order to make a work about violence, she wanted it to be real – something that the audience could feel. During her fight, Marcela experienced the instinctual fear she has aimed to recreate with Agentic Mode.

Curious about how the experience will influence Marcela’s work, I ask her a question in this vein and take a last puff of my cigar. After two hours, I am getting better at relighting it, besides accidentally starting a small blaze in our ashtray by dropping a still lit match into the heap of used matches.

Marcela begins to talk and pauses, taking a moment to consider what she’s going to say. “I think a fight can be art, but I don’t want people to think of [my fight] as art because it takes away from the art that’s already there. This is a martial art people study their whole life for.”

Our conversation comes back to my original question: How do you create artwork about violence that helps audiences understand violence as a lived reality?

“Performance, the idea of making something experiential, is the only thing you can really do.” Marcela speculates, “You’re explaining it in a way that hopefully doesn’t shove it down their throats like ‘We die every day.’ Maybe that’s the only way you can understand, because you’re still making the choice.”

I think again of her describing Agentic Mode as a “slow consensual experience.” Violence is rarely consensual. Like Marcela putting herself in a fighting cage, where she could get seriously harmed, to understand what it feels like to be a part of the fight community, her audience chooses to witness her performance—trusting Marcela to make them experience the mental space of fear that makes violence possible.

“It’s a sport. It’s over. She just wanted to win,” Marcela says soberly, sitting back in the leather armchair.

Her observation, while strikingly succinct, is perhaps the best answer to my questions. We can watch Agentic Mode unfold, allow it to unsettle us and help us understand our instinctual, bodily responses to situations of fear, but it is simply a performance. It ends. Marcela has posed the questions about violence that she wanted to. We have to choose to find the answers.