A Collector's Personal Focus: Discovering the Value of Engagement

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

When an art world colleague mentioned one day that a favorite client of his had an extensive, private collection of art not often shared with the public, I was intrigued. I never tire of profiling collectors and how they assemble personal outlets for creative passion. It’s truly one of the highlights of being the publisher of CGN. The difference right now is that due to COVID-19, I would not be able to see this collection in person. Like so much else these days, this collection would have to be experienced virtually – emailed images digested from my laptop. While that sounded discouraging at first, it allowed for a more lingering, ultimately still first hand look at one man’s devotion to a top notch collection displayed over five locations, including two residences in Chicago, a suburban office on the North Shore, and two homes in California.

The collection contains approximately 120 works of art, and currently nothing is hidden away in storage. It spans mediums, from figurative paintings to multimedia works, as well as from collage to sculpture, but the collector, who opted to remain anonymous for this interview, says that most of the art may be classified as post-1980 work by American and European contemporary artists. Adding to the range and eclecticism of the collection are antiquities, fossils, Chinese cloisonné, medieval reliquaries, textile garments, and original comic book art. And while I was unable to see the collection first-hand, it may be viewed by private appointment.

The collector’s interest in art was piqued in college, and over time, he discovered he wanted to be surrounded by art. As he found his personal focus, he has approached art collecting as a life-long education in creativity and deliberate engagement.

CGN: Initially what helped you learn about art?

Collector: Like many humanities majors at liberal arts colleges, I took a few art history classes, one of which was a fine arts course titled Twentieth Century Painting, which the students jokingly named “Spots and Dots.” Although this was during the late 1970’s, the art I surveyed in the course seemed to end abruptly at 1960’s minimalism. I wondered what important art had been produced in the intervening decade, so I asked a friend, an art history major, what she knew. Her response was memorable: “Not much…Some guy crucified himself on a Volkswagen.”

My interest in art generally, and more specifically contemporary art, began with that college course, despite where its coverage ended. After graduation I took a job in banking in Los Angeles. On the weekends I would go to museums and galleries, just looking and learning.

CGN: When did you get started enjoying art and then collecting it?

Collector: My interest in collecting art really began when I happened to see the photos of Henry Geldzahler’s New York apartment in the September 1982 issue of Architectural Digest. Several qualities about that apartment appealed to me. For one, the art was displayed informally. Until then I had thought art was only displayed in ornate frames and in fancy, decorated homes, but here was art almost haphazardly arranged, with pieces placed on floors and in bookshelves. Second, there was a lot of art in the small apartment. He had artwork everywhere – on walls, atop tables, and in every corner. Finally, he had two artworks by young, then-unknown artists that really knocked me out: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Geldzahler had just acquired the paintings at the P.S. 1 Queens exhibition New York/New Wave. I thought, if art this novel and exciting is being created now, then I want to start a collection. Basquiat and Haring were already priced out of my reach, so I started looking at local LA artists. Shortly thereafter I acquired my first painting, a small work by artist Jeffrey Vallance. I got a cash advance against my credit card to buy it. The painting is still displayed in my Chicago condo.

CGN: You own a wide range of art, from large-scale work by internationally known blue-chip names to smaller-sized pieces, many by Chicago-based artists, among others. How do you manage the installation of such a blend of work?

Collector: I don’t think about how a work will be displayed when I purchase it, and this indifference has led to some interesting issues. I purchased a Paul McCarthy work, Bavarian Deer, a few years back. I knew it was big, because part of its impact is its scale – the artwork is a small 1960’s postcard image of a deer, blown up to monumental proportions. It wasn’t until the work arrived in Chicago though, that I realized it wouldn’t fit in my building’s elevator. My art installer, Dennis Callahan, arranged with the building to ‘ride the elevator,’ placing the work on top of the elevator cab and riding with it. Then we decided to hang the work in front of a window, which was the only space for it in the condo. Installed it looks amazing: a nostalgic image of innocence, enlarged to nearly billboard-size.

CGN: Do you look for conversations between the works?

Collector: I sometimes arrange works thematically. For example, in my office I have two drawing collages by Tony Fitzpatrick, purchased from the artist. While I was visiting with Fitzpatrick, he mentioned a Chicago artist in his own collection, Jared Joslin. So I purchased one of Joslin’s works, Panther and the Zebra, and it is installed next to the two Fitzpatrick pieces.

CGN: How would you describe the focus of your collection now? What’s it like to live among this mix of art that so many only see in a museum?

Collector: The focus of my collection now is 1980’s American Contemporary. Initially I approached collecting the way most consultants advise: buy what you like. For me, though, this was unfocused, because I found that I liked a lot of art. So I needed to narrow my range, and when I looked at my collection I decided that the works that meant the most to me were those made by American artists prominent when I first became interested in art in the early 1980’s: Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, Susan Rothenberg, Robert Graham, Robert Therrien, Jim Dine, and others.

Art of the 1980’s has a vibrancy, and that energy spilled over into music, fashion and performance. I think the influence is ongoing.

CGN: You’re still an active collector today. How do you learn about and discover art now?

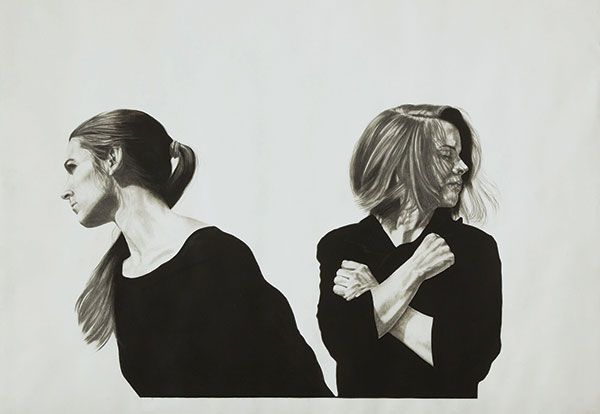

While my 1980’s focus continues, I have added a handful of works each year from current artists, purchased from galleries. Most recently, I’ve acquired two Jan-Ole Schiemann paintings from Nino Mier (LA) and Kasmin (NY), a Jenna Gribbon work from Fredricks & Freiser (NY) and a Paul Sietsema work from Matthew Marks (LA).

CGN: Where do you primarily buy art – through galleries, auctions or art fairs?

Collector: For works from the 1980’s, I am primarily purchasing at auction. More current works I purchase through galleries, and occasionally at art fairs. I go to very few fairs, only Frieze New York, Frieze Los Angeles and EXPO CHICAGO.

CGN: Your focus, once you decided on one, is very personal.

Collector: I love living with these works, and spending time with them. 20 years ago, the comedian Steve Martin displayed his art collection in Las Vegas, and he wrote and narrated the audio tour guide. A point that he made was that an artwork succeeds when you can stare at it for hours and find meaning, but you know in the end you’ll never fully understand it. He said it better, and funnier, but that’s the gist, and I agree with him.

One issue I am conscious of is that private ownership of art deprives the general public of viewing those works. But I don’t think it applies to the works in my collection. I tested my hunch a few years ago by offering to have my estate leave my collection to a well-known modern art museum, which shall go unnamed. The museum agreed to accept the collection, but only if they were free to sell any or all of the works. Thus, the market has spoken: my art works are very meaningful to me, but they are not necessarily rare, and their private ownership does not deprive patrons of the ability to view works that might be deemed enormously important.

CGN: What do you think about art for investment?

Collector: When it comes to art, one needs to be agnostic as to intrinsic value and investment potential. I don’t think about art as an investment, except to the extent that I do insure the collection and try to keep track of its value for that purpose. Over the past 40 years of collecting art, I’ve certainly purchased works that have increased in value, and conversely some of the works I’ve purchased probably have very little resale value.

I guess the way I look at the value of art can be summed up by a story about a recent acquisition. Many years back, I asked an artist – who happened to live next door to me in LA at the time – the price of one of his works, a favorite of mine. The price he named was more than I could afford then. Recently, I finally acquired that work from that same artist through a NY gallery for 30 times the price the artist stated so long ago. It doesn’t bother me that I had to pay so much more for it now, I’m just happy to have it in my collection. I ended up sending the artist an email congratulating him for holding the work so long, and in the process earning a ten percent annual compounded return for 38 years!

CGN: What would you tell a visitor about your collection, as well as about collecting in general?

Collector: Since my collection is so varied, I would speak about each work individually rather than the collection as a whole. In fact, rather than speaking I would hand the visitor an information page I’ve prepared for each of the works. It includes information that would typically be shown in an auction catalog, for instance: date created, media, and provenance. I have tried to include, in a condensed version, thoughts and ideas on the artists, and sometimes specifics about the actual artwork in the collection, on a page that the visitor can read while looking at the work itself. I re-read these notes myself from time to time.

As far as collecting in general, I would suggest buying what you like; but, again, at least in my case, it helps to have a focus. You might build a collection around a certain time period, a genre, or different stages in a single artist’s life and work. I would also advise finding out as much as you can about the artists in your collection, including auction notes, criticism, films, and interviews. For example, to fully understand a Schnabel plate painting I think it’s crucial to watch Michael Blackwood’s important 1982 documentary A New Spirit in Painting. Likewise, my Eric Fischl painting The Chair, The Bed, Getting Ready had much greater resonance for me after reading his autobiography Bad Boy. I would also recommend three great books on how to view and understand modern art: Robert Hughes’ The Shock of the New, Leo Steinberg’s classic Other Criteria, and Calvin Tomkins’ amazing book The Bride and the Bachelors, which I keep coming back to, and have now read several times. Also, go to galleries and speak with the representatives.

I never understood Nan Goldin’s photographs until her work was explained to me by Mike Davis at Matthew Marks. Once decoded, I fell in love with these photographs, and recently added Goldin’s 1991 photo Guy at Wigstock to my collection.

CGN: What kind of conversations have started about the art in your collection?

Collector: Almost everyone that visits the collection tells me which work is their personal favorite. Some tell me which is their least favorite! Now, when I have visitors, I do ask them which is their favorite, but I also ask them: Why? What do you like about your favorite work in the collection? What are the qualities of the work that make it your favorite, or least favorite? I enjoy this discussion and have learned from it too. And I do ask people to take their time while visiting the collection. There is a terrific article written by art historian Jennifer Roberts titled The Power of Patience. In it, she argues, convincingly to my mind, that collectively we have lost the ability to focus in a slow, engaged way – what she calls ‘immersive attention.’ Its only at this slow-paced, immersive engagement with the work that I believe art truly reveals itself.