A Man Walks Into a Museum: For Tony Fitzpatrick, 2021 is a Return to More Than Before

Tony Fitzpatrick. Photo: Peter Rosenbaum

Fall 2021 CGN Cover Interview.

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

Fresh from a positive report from his cardiologist, artist Tony Fitzpatrick invites me to sit down and indulge in some fried chicken and cake. Following a 2015 heart attack Fitzpatrick, at 63, is full of life and fire. A widely-known creative force in Chicago and well beyond, the artist says he was given a second act (or third, or fourth, if you listen to his stories of previous close calls) in order to keep making art.

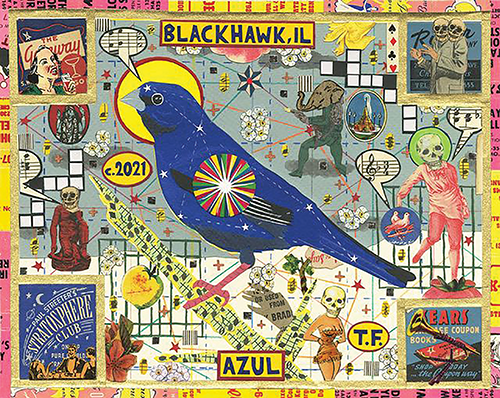

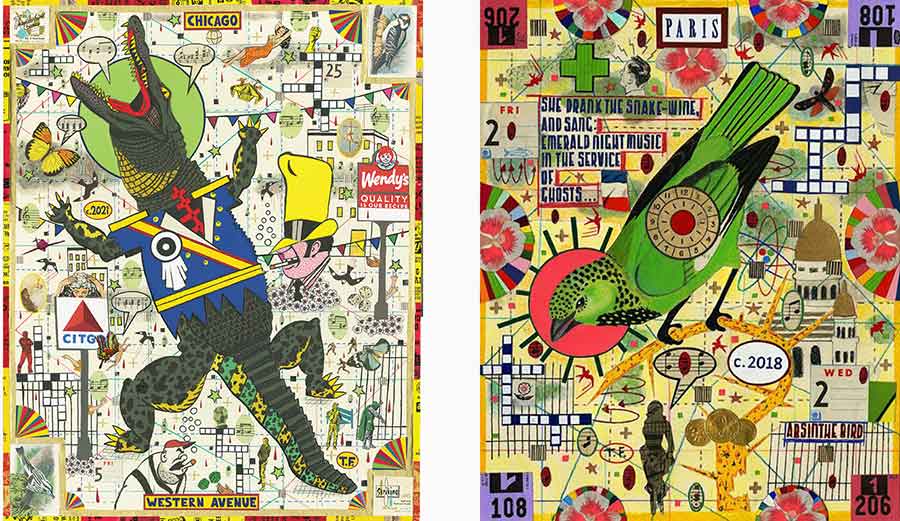

Fitzpatrick’s stories are legend, and he loves a listener. More than that, he loves an audience. He’s sure to get one this October, when he opens Jesus of Western Avenue, an expansive exhibition taking place at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art in suburban Glen Ellyn. The artist will also be publishing Apostles of Humboldt Park, a book featuring a collection of work Fitzpatrick created in isolation: signature drawing collages of birds he’s observed and admired throughout Chicago’s famed west side park.

As much as Fitzpatrick loves connecting with people and sharing his stories, from Facebook to a theater stage, he seems most at home in his west side studio, working on his latest collages as well as directing deliveries and shipments of art, hosting visitors or introducing artists and collectors through exhibitions at The Dime and T.F. Projects. If Western Avenue is the solar system, Fitzpatrick might be its sun. There is a gravitational pull that keeps everything in orbit around this particular star.

Fitzpatrick wears his heart (tatooed) on his sleeve. There is no speak softly and carry a big stick. There is if you don’t like what he says, you can see yourself out. What pours from Fitzpatrick’s stream of unselfconsciousness are positions on a multitude of topics. When Fitzpatrick took to Facebook during 2020’s lockdown to encourage fellow citizens to be masked and socially distant, he chose the hashtag #staythefuckhome over the more pedestrian, #StayHomeStaySafe.

Art, not surprisingly, occupies many of Fitzpatrick’s areas of opinion. For the dozen or so years I’ve known him, Fitzpatrick has frequently shared that he dislikes art fairs. The multi-day, scene-obsessed frenzy they can generate has represented, for him, the apex of all that can be obscenely money-driven, ego-centric and just plain ridiculous about the art world. However, during a recent shared ride to attend the funeral of a friend, Fitzpatrick had the chance to tell Tony Karman, founder of EXPO Chicago, one of the country’s most prominent contemporary art fairs, that he sees fairs in a different light now.

Where he once ranted at the affront of an art marketplace that seemed to rule at the expense of true creativity and art appreciation, he says he now realizes that when many people gather for fairs there are celebrations of art as well as unparalleled opportunities for idea sharing and artist recognition; not everyone is a self-interested speculator. The professional convergence and standards set at the best art fairs have facilitated timely and productive discussions and projects that benefit a broader public. Fitzpatrick sees Karman, amidst a landscape more challenging than ever, as a man trying to harness the best forces of the market in order to bring people together – to Chicago – in a way that positively moves art and artists forward together.

“I think Tony’s been a good steward of culture in this city. He’s the most brutal optimist you’ve ever met in your life. It’s infectious,” Fitzpatrick exalts.

This about face is just one sign that Fitzpatrick continues to be full of surprises. He considers, “I got a new lease on life from heart surgery, and I lead a really different life now. I swim every single morning. I don’t eat fried chicken a lot (just today).” His opinions, as well as his habits, are like the man himself: sometimes stubborn, but never immoveable.

“In the last five years I realized the glass is half full. I wasn’t looking for the good, but I found it. I learned that even just walking around Humboldt park could do me a world of good. I’ve gotten into birding in a big way and also become kind of an activist on behalf of birds and the environment.”

With more time to himself in 2020, except for socially distanced jigsaw puzzle deliveries via pizza peel to friends and clients, Fitzpatrick says he had the chance to care more about the local and global environment and how change relates to weather as well as his much loved local birds. “That’s one issue I think we really have to face as a culture and as artists – being better stewards of our planet. Everything’s changed. I think COVID kind of made us somebody else.”

Fitzpatrick has also been a sort of activist on behalf of emerging artists who need mentoring support and exhibition exposure and has launched several gallery spaces in Chicago, from partnering on AdventureLand, to founding The Dime, and the newer T.F. Projects. In each case he has sought to adjust the traditional gallery model from an even split between dealer and artist to one that favors the artist. Fitzpatrick recently appointed a new full-time director, Rachael Raab-Wasaff, to manage the galleries and lead from a female vantage point, while also managing Fitzpatrick’s career, freeing him up to work on his art.

Blackhawk, Illinois Indigo Bunting (Dreaming of Stars), 2021

Of course, Fitzpatrick is really never just making art. He’s also designing puzzles, publishing books, collaborating on public art–he unveiled a large-scale mural for Steppenwolf Theater Company this summer–and preparing for what he says will be his final museum show this fall, at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art.

“I feel really good about the exhibition,” says Fitzpatrick. “Right now we have at least 75 pieces in it, so far. We may have to cut, but we’re working with a lot at this point.”

The Cleve Carney Museum of Art, formerly the Cleve Carney Art Gallery, part of the College of DuPage and the McAninch Art Center, underwent a renovation and expansion of its galleries as well as a name change in 2019, in anticipation of Frida Kahlo: Timeless, which, along with Fitzpatrick’s show, was delayed for a year due to the pandemic.

When I ask about Fitzpatrick’s connection to the museum, he reveals, “I started caddying for Cleve Carney’s father, Marv Carney, in the 70s when I was about 12.” Looking across the table at Fitzpatrick, wearing his favorite White Sox hat and with gray in his beard, his fair skin mostly obscured by colorful tattoos, I am trying to picture him as a country club caddy, let alone a pre-teen. Fitzpatrick confirms he was never a golfer. “Why would I wear funny pants and chase a little ball around?” he asks me. He explains, however, that he was particularly good at reading greens, a skill he possessed because his drawing acumen helped him understand planes and trajectories.

Fitzpatrick emphasizes that he learned a lot from that time. “You wouldn’t think it would be the job that most formed me, but it did. I learned how to win graciously, and how to lose gracefully.” Fitzpatrick also got to practice the art of listening (to more than a few dirty jokes), as well as getting, and holding, someone’s attention – skills that would all be put to use when he would later perform and tell stories in theaters and on film.

He says, “I had a remarkably bad attitude, but Marv liked me because I read his putts, and they played for money.” Following some remarks on the course one day–Carney let Fitzpatrick know he needed a haircut as well as an attitude adjustment–when asked what he was going to do with himself in life, Fitzpatrick responded, “I wanna be an artist.” To which Carney exclaimed, “Fuck. You’re not going to make any money. My kid’s into that. He just got out of law school. Every damn dime he makes, he spends on art.” Carney offered to introduce Fitzpatrick and his son the next time he was out golfing.

However stern Marv was, Fitzpatrick says, Cleve was a lot of fun. “If I were to liken him to something in nature, it would be a pond full of otters.” When he did get to know Cleve, eventually Fitzpatrick showed him some drawings, and Cleve, in his late 20s at that point, responded by telling the young artist about many others, such as the German expressionists, and the artists of the Weimar Republic. When Fitzpatrick shared that he wanted to learn how to make etchings, Cleve pointed him to study Hogarth, and Picasso. “He really came to me with the right things at the exact right time [in the 70s.] When I started making a name for myself in the 80s, Cleve was the first guy to come to my studio, and every time he came, he would buy something. He was just unbelievably kind and supportive of me.”

Cleve Carney built a major art collection over the years and championed a wide range of nonprofits and causes throughout Chicago. His 2012 donation of $1 million in cash and art to the college helped establish the Cleve Carney Arts Gallery which became the Cleve Carney Museum of Art in 2019. Fitzpatrick knew he had to do this exhibition, the one he says will be his last museum show, because he credits the support of this one man with making him an artist.

*

Left: Western Avenue (Street of Crocodiles), 2021; Right: The Emerald Bird (Absinthe Bird for Lenora Carrington) drawing collage, 2018

I’ve heard Fitzpatrick talk about lasts before, so knowing he’s looking to keep going, following his heart attack, rather than call it quits, I press him if he really means it. Does he wonder what new, impossible to pass up offer could still come along?

“The museum thing, for sure it’s the last,” he responds. “It’s time to get out of the way for people who don’t look like me. If I deal myself out of that equation, then some institutional wall space becomes available for somebody else. I think it’s important for us to create some equity, and it starts with every single artist.”

He emphasizes the significance in artists recognizing that they are each other’s advocates as well as worthy of accepting each other’s support. “The one thing the community has to realize is the most valuable assets we have are each other. Most things one artist cannot do by themselves. You put four or five of them together, and you can move mountains.”

*

Art work for Fitzpatrick's mural, Night and Day in the Garden of All Other Ecstasies.

Fitzpatrick’s new Steppenwolf Theater mural, titled Night and Day in the Garden of All Other Ecstasies and completed this spring, may also be his last mural in Chicago. Created in honor of the theater’s former artistic director, and Fitzpatrick’s friend, Martha Lavey, it represents the evolution of the storied company. At 12 feet high by 76 feet long, the mural hits some firsts for Fitzpatrick–his first outdoor mural and his largest work to date. Artist Danny Torres is credited with the laborious process of digitizing Fitzpatrick’s images for the mural inch by inch, which took him six weeks before they could be transferred to tile by a company in Italy. The quality and durability of the images on tile means that the mural won’t be as vulnerable to degradation by sun or weather. Says Fitzpatrick, “I think it’s a future of public art. I love the romance of painting onto something, like Michelangelo, but how often is most of that covered up?”

Coming off of the Steppenwolf mural, Fitzpatrick and Torres started their own company–Fitzpatrick, Torres, Humboldt, Caballo–and are now looking for opportunities around the country and the world. Though this is supposed to be the last one they do in Chicago, time will tell. Either way, their work will not end.

*

Whereas some people become more stubborn with age, swearing off new things, and people, Fitzpatrick thrives on fresh energy. His friendship and business partnership with Torres, who is about half Fitzpatrick’s age, was also borne from what followed Fitzpatrick’s heart attack. Torres’s aunt, a cardio rehabilitation nurse at St Mary’s Hospital where Fitzpatrick received care, called Fitzpatrick. He recalls, “She just says, ‘This is Rosa, who restored you to life. I want you to meet my nephew, who is a marvelous artist.’ The minute we started talking, it was like we knew each other. We were already kind of the same.”

Fitzpatrick liked Torres and wanted to support him, so they talked about taking 18 months to get enough work ready to hang at AdventureLand, the gallery which used to be where T.F. Projects is now. Torres sold out his first show on the opening night. Not long after that was when Steppenwolf approached Fitzpatrick about the mural for their new building. He knew he could make the maquettes but he would need a top crew of artists to work with to execute it on a grand scale. Torres was his first choice. And once COVID altered the project’s entire timeline and prospects, just the two of them were mainly left to see it through.

“No one could say they knew what [COVID-19] was yet,” Fitzpatrick recalls, “We were kind of lost for a while, until Mike Tobin, the head of Steppenwolf’s board, introduced us to the guys at Imola Ceramica.” Around for centuries, the company became known for fabricating decorative porcelain and ceramic tea sets before delving into cutting edge imaging about 30–35 years ago. That connection made the Steppenwolf mural’s production possible, and it also revealed new collaborations for Fitzpatrick and Torres, as well as any future players who come into their orbit.

The mural commission was obviously a significant artistic and business win for Fitzpatrick and his team, but what he says he finds most valuable is the work as public art in Chicago that will last long after he is gone.

“To do this in a public way, where people don’t have to pay a dime to see it? I love that.”

Jesus of Western Avenue is on view at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art: October 16–Jan 31, 2022

Tony signing limited edition posters for Steve Earle's tribune album to his son Justin Townes Earle