The Art of (Medieval) Living in Chicago

By ANNA DOBROWOLSKI

If we click our ruby heels three times and return to a pre-pandemic world, the ‘Dark Ages’ had a bright future. Medieval art influence was everywhere in pop culture, from Vogue to video games. Maybe you remember the Met Gala’s ‘medieval’ theme in 2018, “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination”? That same year CGN interviewed the medieval expert and founder of Les Enluminures, Sandra Hindman, who shared the same optimism in light of an exhibition with the Art Institute featuring nearly 30 manuscript illuminations from her collection.

Within a year, there was another parallel: COVID-19 to the 14th-century bubonic plague. People then and now turned to art not only as a response to but also as a reprieve from not understanding the world around them.

Perhaps the closest thing Chicago has to the medieval world is hidden in the collection at the Newberry Library, housed in a neo-gothic building adorned with gargoyles that allude to the ‘Old World.’

I visited Sandra Hindman in her office in the One Mag Mile building in downtown Chicago to ask some questions. How can we bring that world of scribes and illuminated manuscripts into our buzzing world of instant messaging and AI? What can that world teach our own—and what light can art advisors like Hindman shed on the Dark Ages for their clients?

Somehow the pages from manuscripts on the wall – spawned from another world centuries ago – seem right at home next to the view of Lake Michigan. Hindman’s screensaver is of a miniature of Italian-French poet Christine de Pizan sitting in her study. As we start talking it’s clear that I’m not the only one who feels that there’s much more to appreciate about medieval art. In September, Hindman unveiled a soft rebranding of LE, and launched a parallel art advisory, the first of its kind. Both endeavors are intended to help others bring medieval art home. Below is our conversation about the challenges and creative solutions of keeping medieval art alive.

*

CGN: How has the market changed in recent years, and what does that mean for you?

Sandra Hindman: I think it might have changed more in the last five years than in the last several decades. There has been a dramatic shift. In the early '90s there was the rise of art shows. But now there’s a new king and queen: auction houses and art advisors.

Technological advances in general, and the pandemic and lockdown in particular, increased the importance of the internet, including the presence and outreach of big auction houses. Simultaneously there is more money for art in more hands, but the ‘hands’ are too busy to be on the hunt themselves. If the king is the auction house, the queen is the art advisor. Except, there are probably ten times as many art advisors and art advisory ventures than ever before.

CGN: What are some challenges you face running a business of medieval art today?

SH: The expected answers would be: Finding inventory, funding it, finding clients, having enough money to pay all expenses, and purchasing inventory. But in fact, the biggest challenge is different. The Middle Ages seem more distant now than ever before, what with iPhones, iPads, computers, and now Al.

I haven't done even an informal survey, but I wouldn't be surprised if most people, even very "qualified" buyers, are not sure when exactly the Middle Ages was* and what happened during it, not to mention why they should care. I think that teaching people why a connection with the past is important and how (and why) they can live with medieval art in the present is the most challenging part of my business now.

*In case you need a refresher: the Middle Ages in Western Europe were roughly bookended by the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

CGN: How are you overcoming that challenge of making medieval art more accessible to more buyers? Do you have any advice for those learning how to appreciate these objects?

SH: Learn to live with them at home and feel comfortable about them. Christopher de Hamel, author of Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts once wrote “No one can claim understanding of the late Middle Ages who has not read a Book of Hours in bed." Even if you can’t read the physical book in bed, you can read about it – it doesn’t take as much time as you would think!

CGN: Can you provide an example from your collection (like this Posy ring) and walk us through it?

SH: A posy ring originates in the sixteenth century and they appear to be exclusively English (though there are some Latin, French, or Italian ones out there). Shakespeare incorporates them into his Hamlet:

Hamlet: Is this a prologue or the posy of a ring.

Ophelia: Tis brief, my Lord

Hamlet: as a woman’s love”

CGN: What can we learn from a single leaf when the rest of a compendium might be missing?

SH: There is much to glean from a single page. Art is art. The beauty of the page, even a single page that has survived from a compendium, can give us access to great art by world class artists – some of whom remain anonymous forever – that is otherwise not accessible or financially unachievable in a complete codex.

CGN: What piece in your collection has left a deep impression on you lately?

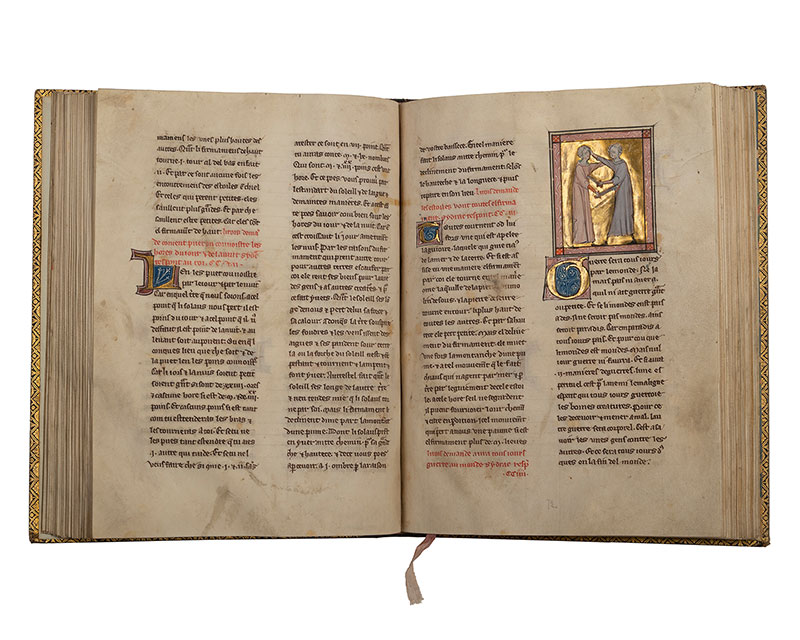

SH: Sydrac’s manuscript. The copy I have*, which has been deaccesioned from an Imperial Russian collection has about 600 questions and answers between Christian philosopher Sydrac and ancient Babylonian king Bokkus to explain the natural world. It contains questions like “How do fish sleep?” “Why don’t the stars fall from the sky,” “Where does fire go when it burns out?” “Can we prolong life?” People are thinking about that one now. There’s another, “Will there always be war?”

CGN: *The Book of Sydrac (Le Livre de Sydrac) Sandra mentions is a imagined dialogue between Christian philosopher Sydrac and ancient Babylonian king Bokkus to explain the natural world in over a thousand questions—a kind of rhymed encyclopedia. It was originally written for the French king in the 13th century. While ‘bad science’ might not make for good literature (answers range from quirky and moralizing to poetic), as art and as an object that survives today, it shows us that how we (mis)understand the world relates to what we read and what we see.

**

CGN: What are you looking forward to?

SH: Two things in particular. The first is: we are engaged in a soft rebranding photography project – using new photos in space with people – through which we are trying to show how you can live with medieval art in the modern world.

In addition to the soft launch, I’m launching a parallel business called Sandra Hindman Art Advisory LLC, which puts in place functions I’ve been doing for decades anyway. But this is a real gap in the art market internationally. Medieval art is a highly specialized field with few experts and the learning curve is simply too steep for most collectors in this busy world. The client who knows modern and contemporary art, or the museum with a manuscript collection but no specialized curator, they often don't know where to turn. I will advise museums on accessioning as well as deaccessioning projects, where there are special needs. A client who wants to gift their collection, I can find them the appropriate outside IRS appraiser and, equally importantly, advise them on what museum or library would be most appropriate as a gift-home.

In other words, one antidote to this fast-paced world is to use these pieces to enter a world previously unknown to us.

#